Kunst&Zwalm is een outdoor traject met hedendaagse kunst. Kunst&Zwalm (27-08-2011 tot 11-09-2011 ) gaat verder dan een aantal kunstwerken in de natuur te plaatsen. Het is een gedurfd experiment waarbij de functies van de kunstenaars, organisators, inwoners en bezoekers zich met elkaar vermengen. De rode draad is de beleving van het uitzonderlijke en idyllische landschap van de Zwalmstreek. Door dit kunstenparcours worden de Vlaamse Ardennen ervaren als een landschap vol culturele diversiteit.

In de editie van 2011 wordt aan de kunstenaars een nieuwe interventie gevraagd waarbij ze de gebruikelijke normen en regels in vraag stellen en een kritische afstand durven bewaren. De interventies van de kunstenaars zorgen voor een visuele en fysieke ervaring en spelen hierdoor met de verhouding tussen tijd, plek, ruimte, kunst en publiek.

De site van het Provinciaal Natuureducatief Centrum De Kaaihoeve fungeert als uitgangsbasis voor een kwalitatief parcours van 12 km in het landschap. Dit unieke traject confronteert de bezoeker met drie landschapstypes waar de verhouding cultuur en natuur telkens verandert: het beschermende natuurlandschap, het historisch aangelegde landschap en het industrieel ontgonnen landschap.

Organisation

vzw Boem, Wegvoeringstraat 115, 9230 Wetteren

Concept

Kunstenaars confronteren met het landschap en hen uitnodigen zich daarop te inspireren voor het maken van een nieuw werk.

Projectnaam Kunst&Zwalm

Kunst&Zwalm is een project, geen organisatie. Dat heeft financiele consequenties maar dat biedt het voordeel dat je niet vastroest in gewoontes. We hebben geen vaste expositieruimte. We zijn met dit kunstproject te gast in de streek. Dat past in onze manier van werken, van omgaan met mogelijkheden: de dingen dienen zich stelselmatig aan.

Selectie

We maken geen selectie van kunstwerken, maar van makers die een interessante invulling kunnen geven aan het project door zich open te stellen voor het landschap en zijn bewoners. Kunstenaars creëren een specifiek werk voor een specifieke plek. We drukken de kunstenaars daarbij op het hart dat ze dit project mogen opvatten als een experiment en dat ze even het eigen traject of carrière los mogen laten. Het is ons streefdoel dat de contacten tussen de verschillende kunstenaars gemoedelijk verloopt.

Contacten bewoners

We hechten er veel belang aan de plaatselijke bewoners te betrekken bij het project. Soms nodigen de kunstenaars de inwoners uit om deel te nemen aan hun artistieke creatie. Kunstenaar Ante Timmermans bijvoorbeeld verbleef zeven dagen bij mensen uit de streek en maakte op het einde van elke dag ter plaatse een muurtekening. Pascale Martine Tayou liet bewoners de mutsen uit zijn geboortestreek in Kameroen opzetten, fotografeerde hen en hing die foto’s op posterformaat aan gevels en omheiningen in de streek. Dergelijke verhalen betrekken de mensen. Bovendien werkt het veel comfortabeler als je kan rekenen op goodwill van de mensen. Landbouwers moeten bijvoorbeeld bereid zijn een stuk van hun landbouwgrond of gebouwen ter beschikking te stellen. Beatrijs Albers en Reggie Timmermans hebben in de editie 2005 een werk gemaakt waarbij een voetbalveld in een bos werd geplaatst. Dat vraagt heel wat voorbereidend werk: grote opkuis, rooien van het bos… Zoiets lukt alleen als de buurt en de betrokkenen je project genegen zijn.

Parcours

De ideale manier om het parcours van Kunst&Zwalm af te leggen is per fiets. Al fietsend de kunstwerken ontdekken biedt toch een andere ervaring. Het gaat om het zoeken naar een ideale verhouding tussen tijd, plek, kunstwerk. Je trekt niet simpelweg van a naar b, maar het onderweg zijn zélf, de gewaarwording van ruimte, vormt een meerwaarde. Je beweegt je naar iets, je bent onderweg, babbelt, kunt indrukken laten binnensijpelen,…

Duur van het project

Vanuit praktisch oogpunt volstaan 3 weken: we kunnen de landbouwgronden bijvoorbeeld, niet langer bezetten. Daarnaast zijn we hier als project te gast in het landschap. Wat ook met zich meebrengt dat we hier geen kunstwerken, installaties, geen relikwieën achterlaten. Het project komt en verdwijnt dan weer. Zoals een goede gast, zonder pretenties.

Publicatie

De meertalige catalogus met meertalige kritische teksten van verschillende auteurs, stellen voortdurend het project in vraag, zij streven naar een groter inzicht en een ruimere benadering van de hedendaagse kunst. Het boek vormt een naslagwerk van het project en wordt enkele maanden na het project voorgesteld.

Eerste contact

De organiserende vzw Boem nodigt de kunstenaars vooraf uit om de eerste indrukken op te doen. De tijd die daarop volgt, gebruiken de kunstenaars om met die indrukken aan de slag te gaan. We vragen aan de kunstenaars een vergaande vorm van betrokkenheid met de plek waar zij hun werk willen ontplooien. Tijdens een rondgang in de zomer van 2010 worden alle mogelijkheden en wensen bekeken en besproken waardoor de kunstenaars de kans krijgen zich intenser in te leven. Deze acclimatisering zal het unieke van de interventie gunstig beïnvloeden. De onvoorwaardelijkheid van het engagement zal de kwaliteit en de eigenzinnigheid van het werk onderstrepen. De kunstwerken zijn het resultaat van een verwerkingsproces.

Opbouw

De opbouw van de werken gebeurt vanaf 16-08-2011 tot 27-08-2011

In een project zoals Kunst&Zwalm moet je in de huid kruipen van het gebied. Onder die huid kan je alleen komen door op een betrouwbare manier te infiltreren en het vertrouwen van bewoners te winnen door rekening te houden met hun regels en met de wetten van de natuur.

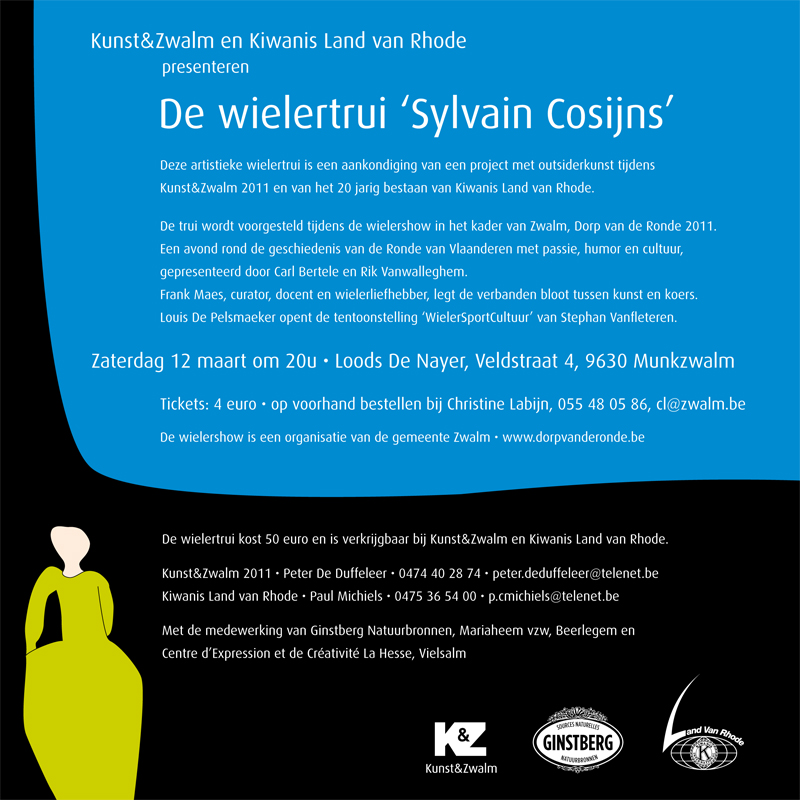

Aan de basis van dit outsiderproject lag de uitnodiging om met een installatie bezit te nemen van een plek, de moestuin van de graaf. De ateliers hout en textiel van La ‘S’ Grand Atelier in Vielsalm en het textielatelier van De Zandberg in Harelbeke, twee artistieke werkplaatsen voor personen met een mentale beperking, gingen samen in zee.

Emmanuel Cordonnier gaf het startsignaal met een reeks houtsculpturen die de gebogen fruitbomen van de boomgaard weerspiegelen. Al snel volgden Rita Arimont, Luc Bienfait, Tony Coopman, Laura Delvaux, Annemie De Paepe, Lindsy Mervylde, Florence Monfort, Nicole Ransbeek en Mieke Vanhessche, elk met hun eigen werk. De ‘tuin van de graaf’ raakt zo bevolkt, ingenomen, gevuld met een verzameling zelfstandige, stuk voor stuk unieke vormen die toch met elkaar in dialoog gaan.

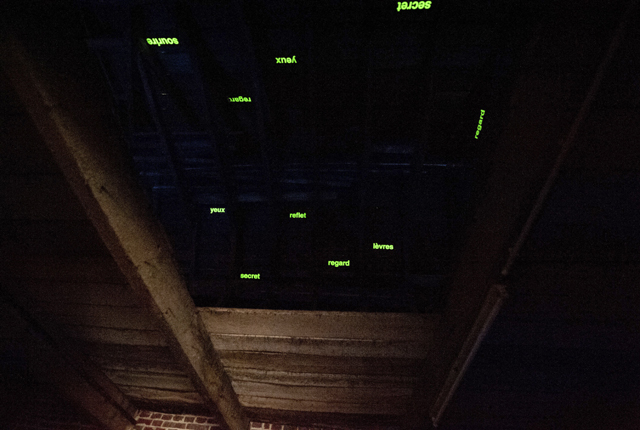

Art in the Dark is een initiatief van Blindenzorg Licht en Liefde, waarbij het publiek zich kan inleven in de wereld van mensen met een visuele beperking. De rollen worden omgekeerd; een blinde of slechtziende gids neemt de zienden mee op een rondleiding in een black box. Hoe is het om te leven in volstrekte duisternis? Kan je dan ook van kunst genieten?

Galerie Transit selecteerde voor de black box twee werken uit het oeuvre van Johan Creten. De beelden van Creten zijn complex van textuur en rijk aan betekenislagen. Ze nodigen van nature uit om aangeraakt te worden. Een bezoek aan de black box kan enkel onder begeleiding en in groepjes van vier tot vijf.

Voor ik het heb over de installaties die te zien zijn op de editie 2011 van Kunst&Zwalm, wil ik eerst even stilstaan bij Double Negative van Michael Heizer (1969-1970). Dat werk bestaat uit twee gigantische greppels die uitgegraven zijn in een woestijngebied in Nevada en wordt vaak beschouwd als emblematisch voor wat men ‘landart’ gaan noemen is. Die ongelukkig gekozen term werd een makkelijke verzamelnaam voor alle soorten kunst die op het eind van de jaren zestig wegtrokken uit de kunstgalerie naar uitgestrekte maagdelijke ruimtes in de natuur; later ging men er alles mee aanduiden wat verwees naar het ‘zich toe-eigenen van de natuur’ door kunstenaars.

Maar door van die anderszins bijzonder diverse kunstwerken enkel de grootste gemeenschappelijke deler te behouden, kan men er nauwelijks nog iets anders over vertellen dan dat ze ‘de kunst buiten het officiële kunstcircuit hebben laten treden’, ‘een denken over de ruimte ontwikkeld hebben’, of dat ‘het landschap zelf een object van de kunst geworden is’ – bemerkingen die men vaak hoort.

Ik geloof echter dat die interpretaties wijzen op een verwarring tussen subject en medium. In een bijzonder treffende analyse van Double Negative1, maakt de kunsthistoricus Kirk Varnedoe een interessante kanttekening: hij wijst op het contrast tussen enerzijds de ervaring van het werk vanaf de grond – d.w.z. wanneer men het werk ervaart van binnen uit de greppel – en anderzijds de beschouwing van het werk vanuit de ruimte, bijvoorbeeld wanneer men het werk bekijkt op een luchtfoto.

In het eerste geval ziet de waarnemer de rotsachtige structuur van een afzettingsgesteente, dat gevormd werd door de opeenstapeling van een eindeloos aantal lagen. Een extreem compacte millefeuille, die in archeologische termen staat voor de traagheid van de geologische tijd en van het ontwikkelingsproces van de mens. De luchtfoto daarentegen accentueert een zuivere, eenvoudige vorm – twee gleuven die de aarde doorsnijden – maar ook de kracht, de bruutheid van de menselijke interventie waardoor de greppels tot stand zijn gekomen (Michael Heizer heeft meer dan 200.000 ton steen laten verplaatsen).

Bekeken vanuit dit perspectief bekruipt ons de idee dat de schepping van een simpele vorm geleid heeft tot de haastige en onherstelbare vernieling van een complexe structuur die het resultaat was van een uitermate lang natuurlijk proces. Als we bovendien rekening houden met het feit dat de tegenstelling tussen het gezicht vanuit de lucht en dat vanaf de grond overeenstemt met de tegenstelling tussen een collectieve en individuele ervaring, worden de antropologische implicaties van Double Negative nog meer evident.

De geschiedenis van het panoramisch gezicht vanuit de lucht was een onderwerp dat Kirk Varnedoe bijzonder interesseerde. Hij heeft terecht opgemerkt dat bijvoorbeeld de foto die László Moholy-Nagy in 1928 vanaf de toren van het radiogebouw in Berlijn nam, behoort tot een type van vergezicht dat de drager is van een optimisme dat te maken heeft met de mogelijkheid om de wereld te observeren vanuit een nieuw gezichtspunt dat verondersteld werd meer objectief te zijn. Robert Smithsons Spiral Jetty of de werken van Michael Heizer zijn daarentegen meer verwant met de geogliefen in de Nazcawoestijn en drukken een zeker pessimisme uit wat betreft de toekomst van de mensheid in het nucleaire tijdperk. Die ongerustheid vinden we voor het eerst in 1947 in het gigantische project voor een ‘sculptuur zichtbaar vanaf Mars’ van Isamu Noguchi – m.a.w. kort nadat de eerste atoombommen gebruikt werden.

De werken van Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer en Richard Long moeten we ook confronteren met die van de periode die eraan voorafgaat. In het begin van de jaren zestig was er een eerste generatie van minimalisten – Donald Judd, Carl Andre, e.a. – die vooral gebruik maakte van eenvoudige, neutrale, pragmatische vormen, die binnen de galerie enkel verwezen naar de ervaring van het heden. Kirk Varnedoe merkt op dat op het eind van de jaren zestig, de vormentaal van de minimalisten gerecupereerd werd door diverse kunstenaars die een andere schaal gingen hanteren en die vormentaal transponeerden naar compleet andere ruimtes, precies om een antwoord te bieden op nieuwe bekommernissen.

Het werken met woestijnlandschappen was voor deze kunstenaars dus geen doel op zich, maar een middel om vorm te geven aan nieuwe uitdagingen en om uitdrukking te geven aan hun bezorgdheid over de toekomst op lange termijn van onze beschaving – een bezorgdheid die vreemd was aan het stellige pragmatisme van de voorafgaande periode. Die idee heeft weinig van doen met ‘de kunst uit het museum halen’ en om deze kunstwerken te begrijpen moeten we verder kijken dan de simpele kwestie van de locatie. Dat de kunst wegtrekt uit de traditionele tentoonstellingsruimtes naar onontgonnen gebieden, beantwoordt aan een noodzaak die het louter verleggen van de grenzen van de kunst overstijgt. De natuur is niet het subject van deze werken, maar het medium dat de kunstenaars toelaat een nieuwe betekenis te verlenen aan de minimalistische vormentaal. Werken in de natuur is niet hetzelfde als werken maken over de natuur.

De omweg die ik hier gemaakt heb, leek me noodzakelijk, omdat het evengoed fout is om de werken op de tentoonstelling Kunst&Zwalm a priori te beschouwen in termen van ‘het zich toe-eigenen van het landschap’ of in dat verband te verwijzen naar ‘de integratie in de natuurlijke en maatschappelijke omgeving’, enz. Die interpretatie reduceert hen tot het bevredigen van een maatschappelijke behoefte. De onderlinge confrontatie van verschillende kunstwerken zal naar ik hoop aantonen dat er meer interessante vraagstukken aan de orde komen.

Het werk van Nicolas Durand bijvoorbeeld, behelst geen poëtische uitnodiging om de gedachten te laten gaan over het omringende platteland. Nochtans is het verleidelijk om zich uit te strekken op de uit steen gehouwen ligstoelen die Durand opgesteld heeft naast de grafzerken op het kerkhof van Paulatem.

Voor we verder gaan, stel ik voor dat we even nadenken over wat een kerkhof precies is, aan de hand van de installatie die Wim Cuyvers creëerde voor de editie 2007 van Kunst&Zwalm. Op een kerkhof in de streek plaatste Cuyvers tussen de graven kampeertenten. Dat lokte bijzonder vijandige reacties uit van de lokale inwoners. Het waarom wordt duidelijk, als we rekening houden met het feit dat een tent verwijst naar iets efemeers, naar een nomadische levensstijl, naar de beweging die eigen is aan het leven – begrippen die haaks staan op de ideeën omtrent de dood in de christelijke westerse maatschappijen. Daarin wordt de dood geassocieerd met een ‘eeuwige rustplaats’, die niets van doen heeft met het infame aardse bestaan.

Die voorstelling van de dood is er echter slechts één van de vele mogelijke. In sommige maatschappijen bijvoorbeeld vindt men dat het stoffelijk overschot van een mens moet worden teruggegeven aan ‘moeder natuur’ en dat men het daarom aan zijn lot moet overlaten. In andere gemeenschappen worden de beenderen gebruikt voor de vervaardiging van wapens of sieraden. Bij de boeddhisten van Tibet en Nepal wordt het stoffelijk overschot in stukken gehakt en als voedsel voor de vogels neergelegd.2

Het menselijk lichaam speelt dus bij talrijke maatschappelijke groepen een rol in de levenscyclus. Dat is anders in het christendom, waar de grens tussen leven en dood veel hermetischer is. De eeuwenoude praktijk van het begraven van het lichaam bij de christenen is gebaseerd op het geloof in de verrijzenis van het vlees. De eerste christelijke vorsten leverden heel wat inspanningen om de praktijk van crematie uit te bannen, precies omdat het lichaam geacht werd ‘in alle glorie te verrijzen’ na de dood.

Diezelfde bezorgdheid om het lichaam te beschermen, is ook de reden dat vanaf de vroege middeleeuwen de begraafplaatsen ingericht werden naast de kerk. We kunnen stellen dat er een scheidslijn bestaat tussen het zichtbare aardse, efemere lichaam en het stoffelijk overschot dat de zetel is van de ziel en dat begraven en aldus beschermd wordt in de verwachting van het eeuwige leven. Die scheidslijn wordt volgens mij precies gesuggereerd door enerzijds de verplaatsing van de tuinstoel naar het kerkhof en anderzijds door de vervanging van de plastische materie waaruit een tuinstoel gewoonlijk is vervaardigd – het materiaal van een wegwerpobject, een materiaal dat nauwelijks iets waard is – door de duurzaamheid van de steen.

Het feit dat Durand zijn installatie bedacht heeft nadat hij verschillende paren ligstoelen had gezien in de tuinen van de Zwalmstreek, noopt ons echter om ook aandacht te schenken aan een ander aspect van het werk.

Bekijken we inderdaad even de installatie in haar context, d.w.z. we beschouwen kerk + kerkhof + grafzerken. Die context doet denken aan de huizen errond, die omgeven zijn door een afgesloten tuin met ligzetels die uitzicht hebben op het meest aangename deel van het landschap. De kerk van Paulatem is niets meer of niets minder dan een huis – dat overigens gedeeltelijk herbouwd is met bakstenen – en dat omgeven is door een omheind, groen terrein. De grafzerken liggen er evenwijdig aan elkaar en zijn eveneens georiënteerd op het platteland. Men kan niet anders dan getroffen zijn door de overeenkomst. Daarnaast wil ik even de eufemistische term ‘laatste rustplaats’ in herinnering brengen: een term die soms wordt gebruikt om te verwijzen naar het kerkhof. Bovendien is er het beeld dat we net hebben geëvoceerd van de kerk als plek waar de doden bescherming vinden. En dan is er ook nog het woord voor kerkhof in Romaanse en Slavische talen. Het Franse woord cimétière bijvoorbeeld is afgeleid van het Latijnse coemeterium, dat zelf terugaat op het Griekse κοιμασθαι , dat ‘slapen’ betekent.3 Ten slotte wil ik er ook op wijzen dat, net zoals iedereen zijn eigen stoel heeft in de tuin, elk individu een apart graf wordt toegewezen, want in het westen is het leven net zoals de dood een zaak van individuen. De configuratie van de grafzerken in de ruimte is om die reden onderworpen aan dezelfde regels die de afstand tussen de levende individuen regelt.

We komen daarom tot het volgende besluit: in onze maatschappij zijn leven en dood strikt gescheiden, maar paradoxaal genoeg worden beide op dezelfde manier genormeerd. Onze grafzerken zijn alle volgens hetzelfde model geconcipieerd, maar hoe zit het dan met die compleet identieke tuinstoelen en de tuinen waarin die staan? De tuinen zijn omgeven door een omheining die het huis bescherming biedt en het afzondert van dat van de buren, dat nochtans gelijkaardig is. De muur omheen de tuin beoogt misschien hetzelfde doel als het muurtje rond het kerkhof, namelijk wie er niet thuishoort buitensluiten. Het muurtje rond het kerkhof herinnert inderdaad aan het feit dat gedurende lange tijd men moest overleden zijn in de schoot van de Kerk om het privilege te kunnen genieten op het kerkhof begraven te worden. Daarmee wordt de gelijkenis tussen de grafzerk en de ligstoel beklemtoond: beide moeten een context scheppen voor het lichaam – m.a.w. het leven en de dood zijn onderworpen aan eenzelfde systeem van normen.

Durands werk behelst dus helemaal geen uitnodiging om het landschap te contempleren, maar wel een uitnodiging om na te denken over de manier waarop we onze levensruimte organiseren (en de ruimte voor de dood, wat op hetzelfde neerkomt). En dat is volgens mij heel wat interessanter.

Het werk van Adriaan Verwée daarentegen representeert niets. Het is veeleer op het zintuiglijke vlak dat de installaties van Durand en Verwée elkaar vinden.

Op een soort steiger of ‘ponton’ aan de rand van een bos heeft de kunstenaar verschillende elementen neergezet: een structuur die vervaardigd is met houten latjes, die loodrecht op elkaar staan; achteraan zijn er rechthoekige gipsplaten op elkaar gestapeld; ten slotte is er aan de voet van deze kwetsbare installatie een hoop met overschotten van dezelfde gipsplaten (verschillende rechte hoeken zijn zichtbaar).

We hebben dus te maken met drie soorten assemblages. De onderdelen van de houten structuur zijn aan elkaar genageld. De samenstellende delen van de gipsconstructie rusten alle op elkaar. De overschotten gipsplaat liggen gewoon op een hoop opgestapeld op de grond. Die stapel met stukken gipsplaat is ongetwijfeld het minst fragiele onderdeel van de drie, hoewel de stabiliteit ervan enkel wordt verzekerd door de wet van de zwaartekracht.

Het volstaat een blik te werpen op de eerste twee elementen om de kwetsbaarheid ervan op te merken. Slecht weer volstaat om ze te doen omkieperen. De meest stabiele structuur is dus paradoxaal genoeg de ingestorte stapel. Die stelt nochtans datgene voor dat niet stand heeft gehouden, de mislukking, het afval van een maatschappij die de voorkeur geeft aan gecontroleerde, regelmatige bouwwerken – zoals de assemblage van gipsplaten die loodrecht op elkaar staan en waaronder Verwée zorgvuldig meetinstrumenten opgeborgen heeft. Op de platen heeft de kunstenaar ook drie vierkante glazen ruiten neergelegd en een aantal metalen stangen om, naar hij zelf zegt, ‘de werkbank van een lijstenmaker’ uit te beelden, m.a.w. van een man wiens job het is om objecten een plaats te geven in een georthonormeerd kader, d.w.z. een frame met loodrecht op elkaar staande zijden.

Daarbij vergelijken vertegenwoordigt de willekeurige opstapeling van stukken gipsplaat datgene wat aan de norm ontsnapt en dat men gewoonlijk liever verbergt, bijvoorbeeld met een dekzeil – en dat is precies wat de kunstenaar opgehangen heeft aan de takken van een boom naast de installatie. Het is alsof hij daarmee de hoop afval wil accentueren en ons er wil aan herinneren dat om een regelmatige vorm te creëren men steeds moet snijden, waarbij steeds noodzakelijkerwijze afval ontstaat.

Door een gelukkig toeval is het rechthoekig stuk glas dat Verwée op de houten structuur had gelegd door de wind in duizend stukjes gebroken. De kunstenaar was echter zo verstandig om ervoor te kiezen de scherven onberoerd te laten. Want zoals bij de afvalhoop, is het ook hier de zwaartekracht die het haalt op de opgelegde orde.

Het is dan weer geen toeval dat Verwée besloot om zijn installatie te maken op de grens – gemarkeerd door een muur – van een mooi geordende boomgaard en een bos kreupelhout, waar de natuur zijn rechten opeist. De installatie staat in feite juist daar waar de muur ingestort is. En het is misschien evenmin toeval dat de ruiten in de installatie niets anders weerspiegelen dan bomen die ingepalmd zijn door klimop…

De installatie van Adriaan Verwée is het waard om geconfronteerd te worden met het werk van Stéphane Cauchy. Het werk dat deze kunstenaar geïnstalleerd heeft in de vijver voor het kasteel van Beerlegem, is het resultaat van de samenvoeging van drie objecten: een kraan, (of eigenlijk de arm van een kraan die naar de hemel gericht is), een waterpomp en een emmer die opgehangen is aan het uiteinde van de kraan. De pomp vervoert water langs de arm van de kraan. De emmer wordt daardoor gevuld, tot het gewicht van de vloeistof de emmer doet kantelen, waarbij de inhoud wordt uitgegoten (wat ongeveer elke minuut gebeurt).

Daarbij moet men volgens mij in acht nemen dat emmer, pomp en kraan uitgevonden werden in de oudheid, maar tot op de dag van vandaag voortbestaan, zij het in een meer gesofisticeerde vorm. De installatie maakt ons in de eerste plaats opmerkzaam op het feit dat een maatschappij niet bepaald wordt door de werktuigen die de mensen gebruiken (want de komst van technologisch meer geavanceerde objecten heeft niet geleid tot het verdwijnen van oudere objecten), maar door de manier waarop mensen gebruik maken van de werktuigen die tot hun beschikking staan en die in de loop der tijden steeds talrijker geworden zijn. Een object op zich bepaalt nooit een of ander soort gebruik. Elk van de drie objecten in de installatie heeft op zich een louter utilitaire functie, maar op deze manier samengebracht, wordt de werking van elk geneutraliseerd. De emmer, bedacht om het makkelijker te maken om vloeistoffen te halen en te transporteren, giet hier elke keer weer het water in de vijver door een natuurwet – de wet van de zwaartekracht – die net als bij Adriaan Verwée ten slotte de overhand haalt.

Daarmee zijn we aanbeland bij een tweede idee. De efficiëntie van de kraan, de pomp en de emmer berusten op het beheersen van de wetten van de mechanica, zoals bijvoorbeeld het kunnen sturen van de atmosferische druk bij een pomp. Maar ondanks alle pogingen om de natuurwetten te beheersen, keert het water steeds opnieuw terug naar zijn bron, onder invloed van een kracht die we niet kunnen ombuigen. En heeft Cauchy bovendien zijn installatie niet moeten vastmaken met kabels om te beletten dat ze omvalt onder invloed van – eens te meer – de zwaartekracht?

Op die manier belanden we bij een nieuw thema, waarmee we meteen een licht kunnen werpen op het werk van Arnaud Verley & Philémon. Hun werk heeft de verdienste dat het ons herinnert aan het feit dat ‘kunst maken in de natuur’ niet hetzelfde is als ‘ecologische kunst maken’ (zoals men wel eens hoort), net zomin als ‘anti-ecologische kunst maken’ – het is niet de rol van de kunstenaar om deel te nemen aan het publieke debat, maar wel om de termen ervan te herdenken.

In de installatie van de twee kunstenaars worden enkele zonnepanelen aangesloten op een oude auto van American Motors. Met veel moeite slagen ze erin genoeg energie op te wekken om de autolichten en de radio tot leven te brengen. Men zou zich nochtans vergalopperen om in dit werk een letterlijke kritiek te zien op systemen om zonne-energie op te wekken. Een dergelijke simplistische interpretatie wordt bovendien verworpen door de kunstenaars. Het aansluiten van zonnepanelen op een icoon van de Amerikaanse autocultuur van de jaren zestig en zeventig – in dit geval op een nogal gammele versie – heeft eerder te maken met de diachronische confrontatie van twee werelden en met de productie/consumptie van energie. Door die confrontatie wordt de vraag opgeroepen of de huidige systemen om energie te produceren wel compatibel zijn met consumptieobjecten die dan misschien wel behoren tot een tijdperk dat voorbij is, maar toch blijven voortbestaan tot de dag van vandaag.

De installatie werpt volgens mij de volgende fundamentele vraag op: wordt onze consumptie bepaald door de manier waarop we energie produceren, of is het onze levenswijze die onze energieproductie bepaalt? De media en het politieke discours laten verstaan dat als we onze consumptiegewoontes veranderen, we geen energie uit fossiele brandstoffen meer hoeven op te wekken, en dat omgekeerd het gebruik van nieuwe energiebronnen een wijziging van ons consumptiepatroon zal teweegbrengen.

De installatie van Verley en Philémon suggereert echter op een heel eenvoudige manier – en haar efficiëntie ontleent ze precies aan die eenvoud – dat het probleem complexer is doordat productiewijze en consumptiepatroon onlosmakelijk verbonden zijn. Het werk maakt een einde aan de oude marxistische idee dat de praxis (het geheel van de menselijke activiteiten) de ideologische superstructuur (onze kijk op de wereld) bepaalt. Maar ook het omgekeerde is fout: de idee dat het voldoende is om ‘de mentaliteit te veranderen’ botst met het dagelijks gebruik dat we maken van objecten en met het feit dat objecten blijven voortbestaan – objecten die zoals de auto van American Motors een zekere socio-symbolische waarde hebben.

Het is in die zin dat ik voorstel om het woord ‘reflux’, dat boven de installatie troont, te interpreteren. De idee zelf van een tabula rasa is een utopie en de installatie van Cauchy suggereert net hetzelfde door het meer of min geslaagd samenbrengen van objecten die al eeuwen overleven.

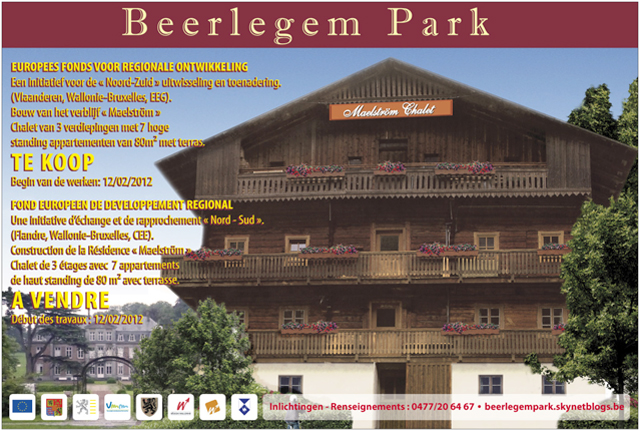

Op dergelijke paden neemt ook Djos Janssens ons mee. Deze kunstenaar heeft voor het kasteel van Beerlegem een reclamebord neergezet, waarop wordt aangekondigd dat er in het park van het kasteel een Zwitsers chalet zal worden gebouwd, dat vervolgens te koop zal worden gesteld. In de gemeente Bastenaken had een dergelijk project reeds verontwaardigde reacties uitgelokt bij mensen die dachten dat het ernst was. Men kan zich voorstellen dat het project een dergelijk onthaal ook in Zwalm te wachten stond, want Janssens kent de structuur van onze representaties door en door.

Janssens’ Zwitserse chalet is inderdaad het tegengestelde van het kasteel – het stelt symbolisch het ‘moderne’ tegenover het ‘oude’, het ‘globale’ en ‘onpersoonlijke’ tegenover het ‘lokale karakter’. Als we ons echter buigen over de geschiedenis van het kasteel van Beerlegem, dan merken we al snel dat die begrippen relatief zijn. Het kasteel werd gebouwd in de eerste helft van de achttiende eeuw in een klassieke stijl met sterke Franse invloeden. In 1872 werd het volledig verbouwd in neoklassieke stijl. Sommige elementen getuigen van een assimilatie van de Franse rococo. Het kasteel is dus niet representatief noch voor een bepaald tijdperk, noch voor een ‘lokale stijl’. Het is wat we metaforisch een composiet zouden kunnen noemen, gemaakt met heterogene materialen die zich opgestapeld hebben in de loop der tijden en die gearticuleerd worden in één en hetzelfde object (wat een verwantschap creëert met de assemblages van Stéphane Cauchy en Arnaud Verley & Philémon).

Wat Janssens met zijn installatie benadrukt is echter dat onze representaties die complexiteit negeren en tevreden zijn met het tegenover elkaar stellen van ‘lokaal’ en ‘globaal’, ‘oud’ en ‘nieuw’. Het feit dat de kunstenaar ervoor gekozen heeft om op zijn reclamebord de afkorting EEG te gebruiken – de oude afkorting van de Europese Economische Gemeenschap – krijgt daardoor een pregnante betekenis. De huidige Europese Unie is bij uitstek het resultaat van een complexe geschiedenis en van een opeenstapeling van structuren die door onze representaties genegeerd worden; de Europese Unie wordt aldus gereduceerd tot een ‘abstracte’ en ‘globale’ macro-organisatie die het tegengestelde vertegenwoordigt van het ‘concrete’ en het ‘lokale’.

Als we ons nu afvragen wat het thema is van de tot nu toe besproken werken, dan is dat noch de natuur, noch het landschap, zoals de lezer heeft kunnen vaststellen. Naar mijn mening wordt in elk werk vanuit een bepaald perspectief verwezen naar een (materieel of mentaal) normatief referentiekader dat de basis is van onze representaties en de manier waar op we onze wereld organiseren. De werken waarover ik het hieronder wil hebben, verkennen de vraag wat kennis is, ieder vanuit een verschillend perspectief.

De vergelijking met een observatorium lijkt me een interessant uitgangspunt als benadering voor de houten structuur die Jo Lathwood gecreëerd heeft in een ongerept veld dat zich uitstrekt zover het oog reikt. Een observatorium is in feite een speciale plek van waaruit men een bepaald object onderzoekt. Een astronomisch observatorium bijvoorbeeld, herbergt instrumenten om naar de hemel te kijken (telescopen en dergelijke). De Franse term observatoire gebruiken we ook voor instellingen die maatschappelijke fenomenen analyseren: men verwijst ermee naar instellingen die onze politieke cultuur onderzoeken, de media of onze pensioenen.

In het observatorium van Jo Lathwood is er niet één, maar zijn er vijf openingen, waardoor er meerdere perspectieven ontstaan. Nochtans zien we enkel door de centrale opening wat er in het veld gebeurt. Door een systeem van spiegels zien we via de andere openingen de lucht, de grond of een deel van het landschap dat we niet verwachten te zien. De spiegels bepalen ons blikveld en ze benadrukken dat door het afstand doen van een uniek gezichtspunt, we ons bewust worden van wat zich buiten beeld bevindt. Hoe meer gezichtspunten er bij komen, hoe meer men zich realiseert dat de beslissing om af te zien van één gezichtspunt arbitrair is. Bovendien geven we er ons rekenschap van dat we de gezichtspunten tot in het oneindige kunnen vermenigvuldigen. Vaak is het comfortabeler om zich te beperken tot één gezichtspunt, vooral als we net als bij de centrale opening van Lathwoods installatie daardoor een uitzicht krijgen op een perfect rechte horizonlijn, d.w.z. op een deel van de werkelijkheid dat zo uitgekozen is dat het onze geest bevredigt.

Het willekeurige van die keuze wordt nog benadrukt door het gebruik van een cirkel – de perfecte geometrische vorm – voor de kijkgaten. Volgens mij toont het werk van Jo Lathwood ons in welke mate wij de voorkeur geven aan één enkele kijk op de wereld, hoewel we zelf weten dat die berust op een illusie. De kunstenaar heeft er precies voor gezorgd dat de spiegels achter de cirkels aan de zijkant zichtbaar aanwezig zijn en die keuze drukt de wil uit om de observator meteen te confronteren met het bedrog dat aan de basis ligt van het mechanisme. Met andere woorden, door het creëren van een observatorium of onderzoeksinstelling voor elk object of elk maatschappelijk probleem – zoals we tegenwoordig doen – isoleren we op een kunstmatige manier dat probleem uit zijn omgeving , terwijl we ons daar goed van bewust zijn. Het referentiekader wordt daardoor zo beperkt dat we ten slotte een simplistisch – en dus comfortabel – beeld krijgen van de werkelijkheid. Dat is wat de rechte lijn in de centrale cirkelopening suggereert.

Een tweede element dat hier speelt is het feit dat in principe een observatorium toelaat om te kijken zonder zelf gezien te worden. Denken we maar aan een militaire uitkijkpost of aan een uitkijkpost in de natuur die de waarnemer verbergt om de vogels niet af te schrikken. In onze tijd een observatorium gebruiken houdt dus in dat we het gezichtspunt verhullen dat aan de basis ligt van de modelvorming omtrent het bestudeerde object. Lathwoods installatie roept vragen op over de onvergankelijkheid van dat tot nu toe goed werkende mechanisme: de kunstenaar heeft in zijn houten hut verschillende kieren aangebracht die de aanwezigheid van de waarnemer verraden.

De titel van het werk, As Far As I Can See, kan geïnterpreteerd worden op twee manieren. In letterlijke zin betekent hij ‘zover als mijn ogen me toelaten om te kijken’, maar in figuurlijke zin betekent de titel ‘voor zover ik kan oordelen’, d.w.z. ‘voor zover mijn hyperspecialisatie in een bepaald domein me toelaat om daarover te oordelen’.

Goele De Bruyn werkt op een erg poëtische manier rond dezelfde vraag. In een bronzen sfeer heeft ze een lamp geplaatst. De bol is ook vol met kleine gaten die de kunstenaar aangebracht heeft na het bekijken van een foto van de achterkant van de maan – de kant dus die steeds onzichtbaar blijft vanaf de aarde. Hoe dichter het publiek deze bronzen maan nadert, hoe meer de intensiteit van het licht verflauwt. Dat proces wordt interessant als men in overweging neemt dat in 1968 de astronauten in een baan rond de maan moesten gaan om de in het duister gehulde kant van de maan te kunnen waarnemen – ze bleven dus verstoken van direct zonlicht…

Deze benadering suggereert dat om tot kennis te komen, de mens heeft moeten verzaken aan de schittering, d.w.z. in letterlijke zin aan het zonlicht en in overdrachtelijke zin aan de fascinerende krachten die de hemellichamen gedurende eeuwen op ons hebben uitgeoefend. De maan van Goele De Bruyn lijkt van ver een schitterende, poëtische en mysterieuze vuurbol, maar net als de maan die we waarnemen van op aarde, lijkt ze van dichtbij een dof object dat zijn structuur en zijn ingewanden toont. Hoe dichter men de bol nadert, hoe meer het mysterie vervluchtigt: het is precies onze nieuwsgierigheid, ons verlangen om een chirurgische kennis te verzamelen van de maan, die het hemellichaam van zijn betovering heeft beroofd.

De Bruyn beklemtoont dat haar maan niet mag gezien worden als een lamp of een decoratief object. Van dichtbij ziet men dat ze de bol aan één kant heeft ingesneden; op die manier reproduceert ze de dwarsdoorsneden die wetenschappelijke handboeken illustreren. Ze heeft ook een deel van de luchtkanalen gelaten die het mogelijk maken om het brons in de vorm te gieten, waardoor ze het fabricatieproces van het werk zichtbaar maakt. Het object, dat op het eerste gezicht enigmatisch lijkt, toont dus al zijn geheimen. Het enige wat overblijft is een uitgedoofd skelet.

We kunnen nog opmerken dat de luchtkanalen lijken op de takken van de bomen die de installatie overwelven, maar ook die gelijkenis herinnert er ons aan dat ze gewoon de sporen zijn die het brons heeft achtergelaten in een object dat nu gestold is, terwijl het plantensap het leven door de takken verspreidt.

Door dichter bij de hemellichamen te komen, heeft de mens zijn vleugels niet verbrand, maar de teleurstelling is misschien een grotere straf dan de dood was voor Icarus.

In deze tekst hebben we enkele van de kunstwerken op de huidige editie van Kunst&Zwalm bekeken. Ik hoop dat ik iedereen overtuigd heb dat het om meer gaat dan het verlangen om de ‘kunst buiten het museum te brengen’ of om ‘zich over te geven aan de natuur’. Ik ben ervan overtuigd dat we dringend de criteria moeten herzien die we hanteren om manifestaties als Kunst&Zwalm te beoordelen. Het toenemend gebruik van termen als ‘ecologische kunst’ of ‘environmentkunst’ lijkt me gevaarlijk, in die zin dat enerzijds dergelijke termen de kunst reduceren tot een eenvoudig probleem van de locatie waar die kunst wordt gemaakt, en anderzijds door het instrumentalisme dat dergelijke termen impliceren. Want als er één ding is dat we kunnen verwijten aan de beoordelingscategorieën die ik hier aan de kaak stel, dan is het dat ze ons ontslaan van de inspanning – maar ons ook beroven van het plezier – om echt te kijken naar datgene wat zich voor onze ogen bevindt.

Ook het gebruik van de Latijnse term in situ om te verwijzen naar kunstwerken die tentoongesteld zijn in de natuur lijkt me problematisch, want die term berust op de idee dat dergelijke kunstwerken meer dan andere rekening houden met de plaats waar ze geïnstalleerd zijn. Tenslotte hebben alle kunstwerken een plaats, in welke tijd ze ook thuishoren. Het feit dat ze bedoeld zijn om van dicht of daarentegen van ver te worden bekeken, dat ze hoog moeten worden opgehangen of op de grond moeten worden gezet, dat ze in een nauwelijks verlichte kerk thuishoren of in een Venetiaans paleis – die factoren zijn van belang om de omstandigheden te begrijpen waarin ze werden geproduceerd of waarin ze worden ontvangen door het publiek, en dus om ze te duiden. Ook de ‘neutrale’ ruimte van de galerie is een plaats en een werk tentoonstellen in een galerie is geen onschuldige gebeurtenis. Met andere woorden, het is de combinatie van kunstwerk en plaats waarover we moeten nadenken. De laatste is niet op zich de drager van betekenis – het is over de manier waarop het kunstwerk ermee omgaat dat we vragen moeten stellen. En dat kan niet zonder een aandachtige observatie van het kunstwerk.

Bénédicte Duvernay

september 2011

1 Kirk Varnedoe, Pictures of nothing: Abstract art since Pollock, Princeton University Press, 2006.

2 Jean Zammit, Pratiques mortuaires et traitement du cadavre ancien (plaidoyer pour une nécro-archéologie), in Revue archéologique de Picardie, Numéro spécial 21, 2003, pp. 185-194.

3 Daniel Ligou, L’Evolution des cimetières, in Archives des sciences sociales des religions, N. 39, 1975, pp. 61-77.

Avant d’en venir aux installations présentées pour l’édition 2011 de Kunst&Zwalm, j’aimerais m’attarder quelques instants sur une œuvre de Michael Heizer, Double Negative. Il s’agit de deux tranchées gigantesques creusées par l’artiste dans une région désertique du Nevada entre 1969 et 1970. Double Negative est souvent considérée comme emblématique de ce qu’on a eu la fâcheuse habitude d’appeler le « Land Art », expression bien commode pour rallier toutes les œuvres qui, à la fin des années 60, se sont déplacées de la galerie vers de vastes espaces naturels vierges, et qui, depuis, désigne encore plus vaguement toutes formes « d’appropriation de la nature » par les artistes. Mais en ne retenant ainsi que leur plus petit dénominateur commun, on ne peut guère dire autre chose de ces œuvres – extrêmement diverses au demeurant – qu’elles ont « sorti l’art de ses circuits officiels », « développé une pensée de l’espace », que « le paysage est devenu l’objet même de l’art », comme on l’entend souvent. Or, il me semble que ces interprétations révèlent une confusion entre sujet et médium. Dans sa très juste analyse de Double Negative1, l’historien de l’art Kirk Varnedoe a mis le doigt sur un point intéressant en remarquant le contraste entre, d’une part, l’expérience de l’œuvre depuis le sol – c’est-à¬dire depuis l’intérieur même de la tranchée – et, d’autre part, sa contemplation depuis l’espace, sur une photographie aérienne par exemple. Dans le premier cas, l’observateur a devant les yeux une structure rocheuse sédimentée, formée par l’accrétion d’un nombre infini de strates. Un millefeuille extrêmement dense donc, qui, en termes archéologiques, figure la lenteur du temps géologique et du processus de développement humain. La vue aérienne en revanche met en exergue une forme franche, sommaire – deux fentes incisant la terre –, mais aussi la puissance, la brutalité de l’intervention humaine qui en est à l’origine (Michael Heizer a fait déplacer plus de 200 000 tonnes de pierres). Posée en ces termes, cette confrontation conduit à l’idée que la création d’une forme simple a impliqué la destruction, rapide mais irrémédiable, d’une structure complexe née d’un processus naturel très long. Si l’on ajoute à cela le fait que l’opposition entre vue aérienne et vue depuis le sol recoupe une opposition entre expérience collective et expérience individuelle, les implications anthropologiques de Double Negative deviennent plus évidentes encore. L’histoire des vues aériennes a beaucoup intéressé Kirk Varnedoe qui a noté avec justesse que, dans une photographie telle que celle prise par László Moholy-Nagy en 1928 depuis le sommet de la tour de la Radio de Berlin, ce type de vue est porteur d’un optimisme lié à la possibilité d’observer le monde depuis un point de vue nouveau, considéré comme plus objectif. En revanche, la Spiral Jetty de Robert Smithson ou les œuvres de Michael Heizer s’apparentent plutôt aux géoglyphes de Nazca et traduisent un certain pessimisme quant au devenir de l’humanité à l’ère nucléaire, inquiétude inaugurée par le gigantesque projet de « sculpture visible depuis Mars » imaginé par Isamu Noguchi en 1947, peu de temps donc après les premières explosions atomiques. Les œuvres de Robert Smithson, de Michael Heizer ou encore de Richard Long doivent aussi être confrontées à celles de la période précédente, lorsque, au début des années 60, la première génération de minimalistes – Donald Judd, Carl Andre, etc. – revendiquait des formes simples, pragmatiques et neutres ne renvoyant, dans la galerie, qu’à l’expérience du temps présent. Ce qui est intéressant alors, fait remarquer Kirk Varnedoe, c’est de constater qu’à la fin des années 60, ce vocabulaire formel minimaliste a été récupéré par des artistes qui en ont modifié l’échelle et l’ont transposé à de tout autres espaces, précisément pour répondre à des préoccupations nouvelles. Investir des paysages désertiques n’était donc pas, pour ces artistes, une fin en soi, mais un moyen de donner forme à ces enjeux nouveaux et de traduire notamment une inquiétude quant à la longévité de notre civilisation – inquiétude étrangère au pragmatisme affirmatif de la période précédente. On est là bien loin de l’idée qu’il faut « faire sortir l’art du musée », et comprendre ces œuvres suppose de dépasser la simple question du lieu. Leur migration des espaces d’exposition traditionnels vers des terrains vierges répond à une nécessité qui va au-delà du seul déplacement des frontières de l’art. La nature n’est pas le sujet de ces œuvres, mais bien le médium ayant permis à leurs auteurs de donner au langage formel minimaliste une portée nouvelle. Travailler dans la nature ne veut pas dire travailler sur la nature.

Si ce détour m’a paru essentiel, c’est que, de la même manière, on aurait tort d’appréhender a priori les œuvres de Kunst&Zwalm en termes de « réappropriation du paysage », « d’intégration dans l’environnement naturel et social », etc., lecture qui les réduirait à la satisfaction d’une demande sociale. La confrontation de plusieurs d’entre elles, je l’espère, révèlera que fort heureusement, celles-ci soulèvent des questions autrement plus intéressantes.

L’œuvre de Nicolas Durand, par exemple, n’est pas une invitation poétique à contempler la campagne alentour. Il est pourtant tentant de s’allonger sur l’une des deux chaises longues en pierre de taille qu’il a alignées, dans le cimetière de l’église de Paulatem, avec les tombes qui s’y trouvent déjà. Avant d’aller plus loin, je propose de réfléchir un instant sur ce qu’est un cimetière en passant par l’installation proposée par Wim Cuyvers pour l’édition 2007 de Kunst&Zwalm. Celui-ci avait disposé parmi les sépultures d’un cimetière de la région des tentes de camping, projet qui avait suscité de vives réactions d’hostilité. Ces dernières s’éclairent lorsque l’on songe au fait qu’une tente de toile connote l’éphémère, le nomadisme, le mouvement propres à la vie, et que ces notions s’opposent à la représentation de la mort dans les sociétés chrétiennes occidentales qui l’associent à un « repos éternel » situé au-delà des turpitudes de l’existence terrestre. Or, il s’agit là d’une représentation de la mort parmi des possibles. Certaines sociétés considèrent par exemple que le corps d’un être humain mort doit être rendu à la « mère nature » et abandonné à son sort. Dans d’autres, ses os sont utilisés dans la confection d’armes ou de parures. Dans la tradition bouddhiste tibéto-népalaise enfin, les êtres humains morts sont dépecés à l’arme blanche et donnés en pâture aux oiseaux.2 Le corps mort rejoue ainsi dans de nombreux groupes sociaux un rôle dans le cycle de la vie, à l’inverse des sociétés de tradition chrétienne où la frontière entre la vie et la mort est beaucoup plus hermétique. La pratique très ancienne de l’enfouissement du corps chez les Chrétiens est fondée sur la croyance en la résurrection de la chair, et si les premiers rois chrétiens se sont appliqués à bannir la crémation, c’est parce que le corps est censé « ressusciter glorieux » après la mort. C’est dans ce même souci de protection des corps que, dès le début du Moyen-Âge, les cimetières ont été accolés aux églises. Or il me semble que c’est cette frontière entre le corps terrestre exhibé et éphémère et le corps mort substrat de l’âme, enfoui, protégé dans l’attente de la vie éternelle que suggèrent, d’une part, le déplacement de la chaise de jardin dans le cimetière et, d’autre part, le remplacement de la matière plastique qui la caractérise habituellement (matière de l’objet jetable, de peu de valeur) par la pérennité de la pierre. Mais le fait que Nicolas Durand ait imaginé son installation après avoir observé plusieurs paires de chaises longues vides dans les jardins de Zwalm doit nous faire prendre en compte un autre aspect de l’œuvre. Regardons en effet l’installation dans son contexte, en considérant l’ensemble église + cimetière + tombes. Celui-ci n’est pas sans rappeler les maisons alentour, flanquées d’un jardin cloisonné et de chaises longues orientées vers la partie la plus agréable du paysage. L’église de Paulatem n’est ni plus ni moins qu’une maison (d’ailleurs reconstruite en partie avec des briques) entourée d’un terrain clôturé et verdoyant, dans lequel se trouvent des tombes parallèles également tournées vers la campagne. On ne peut qu’être frappé par la comparaison. Songeons maintenant à l’euphémisme de la « dernière demeure » parfois utilisé pour désigner le cimetière, et à l’image, évoquée plus haut, de l’église comme lieu de protection des morts – rôle que remplit la maison pour les vivants. Songeons aussi au fait que les pays slaves et latins ont forgé le mot cimetière à partir du terme coemeterium, dérivé du grec κοιμασθαι qui signifie « dormir ».3 Songeons enfin à l’idée que, de la même manière que chacun possède sa chaise dans le jardin, à chaque individu correspond une sépulture, car en Occident la vie comme la mort sont des affaires d’individus, et l’espacement des tombes est lui aussi soumis au respect de la distance proxémique qui règle les rapports entre les vivants. On en arrive à la conclusion suivante: notre société sépare strictement la vie et la mort, mais, paradoxalement, l’une et l’autre sont normées de la même manière. Nos tombes sont toutes conçues sur le même modèle, mais que dire de ces chaises de jardin parfaitement identiques, et des jardins dans lesquels elles se trouvent, entourés d’une palissade qui sépare, protège la maison de celle du voisin, pourtant similaire ? Il se pourrait bien que le mur du jardin assure la même fonction d’exclusion que le muret du cimetière. Ce dernier rappelle en effet que, pendant longtemps, il fallait être décédé dans la communion de l’Eglise pour avoir le privilège d’y être enterré. Ce que met en évidence la condensation de la tombe et de la chaise longue – qui, toutes deux, n’ont d’autre rôle que celui de faire entrer le corps dans un cadre – c’est donc l’idée que la vie et la mort sont disciplinées par un même système de normes. Pas d’invitation à contempler le paysage là-dedans, mais une invitation, bien plus intéressante à mon avis, à considérer la manière avec laquelle nous organisons nos lieux de vie (et de mort, ce qui revient au même).

L’œuvre d’Adriaan Verwée, au contraire de la précédente, ne représente rien. C’est sur le terrain du sens que l’on peut rapprocher les deux installations. Sur une sorte de « ponton » échafaudé à l’orée d’un bois, l’artiste a disposé plusieurs éléments: à mi-chemin, une structure formée de barres métalliques perpendiculaires; au bout du « ponton », des plaques de plâtre rectangulaires posées les unes sur les autres; enfin, aux pieds de cet assemblage précaire, un amoncellement de débris des mêmes plaques de plâtre (plusieurs angles droits sont visibles). On a donc affaire à trois types d’assemblages. Les composantes de la structure métallique tiennent ensemble parce qu’elles ont été soudées. Les parties constitutives de la construction en plaques de plâtre reposent les unes sur les autres. Enfin, les débris de plâtre gisent simplement sur le sol, entassés. Or, ce dernier ensemble est sans aucun doute le moins fragile des trois, sa stabilité étant assurée par la seule loi de la pesanteur. Il suffit de regarder les deux premiers échafaudages pour s’apercevoir de leur vulnérabilité. Des intempéries suffiraient à les renverser. La structure la plus stable est donc, paradoxalement, celle qui s’est effondrée. Elle représente pourtant ce qui n’a pas tenu, l’échec, le rebut d’une société préférant les édifications maîtrisées et régulières, à l’image de l’assemblage de plaques de plâtre orthogonal au-dessous duquel Adriaan Verwée a pris le soin de cacher des instruments de mesure. L’artiste a également posé sur celui-ci trois vitres carrées et plusieurs tiges métalliques pour figurer, selon ses termes, « l’établi d’un encadreur », c’est-à-dire d’un homme dont le travail consiste à assigner aux objets un cadre orthonormé. Par comparaison avec cet ensemble, l’amoncellement aléatoire de morceaux de plâtre représente ce qui a échappé à la norme, et que d’ordinaire on préfère cacher, précisément avec une bâche du type de celle que l’artiste a finalement choisi de laisser pendre aux branches d’un arbre juste à côté, comme pour mieux exhiber ces débris et rappeler ainsi que la création d’une forme régulière nécessite toujours un découpage, donc un rebut. C’est par un heureux hasard que le vent a brisé en mille morceaux la vitre rectangulaire qu’Adriaan Verwée avait posée sur la structure métallique. En revanche, c’est bien l’artiste qui a judicieusement fait le choix de la laisser ainsi. Car comme pour le tas de détritus, c’est finalement la loi de la pesanteur qui l’emporte sur l’ordre imposé. Par contre, ce n’est certainement pas par hasard qu’Adriaan Verwée a décidé d’établir son installation à la frontière – marquée par un mur – entre un verger bien ordonné et un sous-bois broussailleux où la nature reprend ses droits, et plus exactement là où, justement, ce mur s’est effondré. Et ce n’est peut-être pas non plus un hasard si toutes les vitres de l’installation ne reflètent rien d’autre que des arbres envahis par le lierre…

Le travail d’Adriaan Verwée mérite, à son tour, d’être confronté à celui de Stéphane Cauchy. L’œuvre que celui-ci a installée dans l’étang devant le château de Beerlegem résulte de l’agencement de trois objets: une grue (plus exactement la flèche d’une grue pointée vers le ciel), une pompe à eau et un seau suspendu à l’extrémité de la grue. La pompe achemine l’eau le long de la flèche, le seau se remplit donc de manière continue jusqu’à ce que le poids du liquide le fasse basculer et renverser son contenu, toutes les minutes environ. Je propose de réfléchir à la chose suivante: le seau, la pompe et la grue ont tous trois été élaborés pendant l’Antiquité mais existent encore aujourd’hui, sous des formes certes plus élaborées. La première idée que met en évidence cette installation, me semble-t-il, est donc le fait qu’une société n’est pas déterminée par les outils qu’elle utilise (puisque l’arrivée d’objets technologiquement plus avancés n’a pas fait disparaître ceux qui leur préexistaient) mais par la manière avec laquelle elle fait usage des outils à sa disposition, accumulés au cours du temps. En soi, un objet ne détermine jamais un type d’usage: pris un par un, les trois instruments qui constituent l’installation ont une fonction purement utilitaire mais, agencés ainsi, leurs effets respectifs s’annulent. Le seau, conçu pour faciliter l’extraction et le transport des liquides, ne fait plus que reverser l’eau dans l’étang en vertu d’une loi naturelle – celle de la gravité – qui, comme chez Adriaan Verwée, finit par l’emporter. On touche là une deuxième idée. L’efficacité de la grue, de la pompe et du seau repose sur la maîtrise de lois mécaniques, par exemple le contrôle de la pression atmosphérique dans le cas de la pompe. Or, malgré ces tentatives de maîtriser les lois naturelles, l’eau finit toujours par retourner à sa source sous l’effet d’une force que nous ne pouvons infléchir. D’ailleurs, Stéphane Cauchy n’a-t-il pas dû maintenir son installation par des câbles pour l’empêcher de basculer sous l’effet, là encore, de la gravité ?

Nous venons de tirer un nouveau fil qui va permettre d’éclairer le travail d’Arnaud Verley & Philémon. L’œuvre qu’ils proposent a d’abord le mérite de rappeler que « faire de l’art dans la nature » n’est ni faire de « l’art écologique » (comme on l’entend parfois), ni faire de « l’art anti-écologique », que le rôle de l’artiste n’est pas de prendre part au débat public mais plutôt d’en repenser les termes. Dans leur installation, quelques panneaux solaires reliés à une vieille American Motors parviennent à grand-peine à en raviver les phares et l’autoradio. Ce serait pourtant aller un peu vite en besogne que d’y voir une critique littérale des systèmes de production d’énergie solaire, interprétation simpliste d’ailleurs rejetée par les deux artistes. Brancher des panneaux solaires sur une icône de la culture automobile américaine des années 60 et 70 – ici délabrée – revient plutôt à confronter deux mondes de manière diachronique et selon le couple production d’énergie/consommation. Et cette confrontation met en doute la compatibilité des systèmes actuels de production d’énergie avec des objets de consommation qui, bien que représentatifs d’une époque révolue, survivent aujourd’hui. La question fondamentale que pose, à mon avis, cette installation, est la suivante: est-ce notre mode de production d’énergie qui détermine notre consommation, ou notre mode de vie qui conditionne notre production d’énergie ? Médias et discours politiques laissent entendre que changer les habitudes de consommation permettrait d’en finir avec l’énergie fossile ou, inversement, que l’exploitation d’une nouvelle source d’énergie entraînerait automatiquement une modification de la structure de notre consommation. Or, le dispositif imaginé par Arnaud Verley & Philémon suggère de manière très simple – c’est là son efficacité – un problème autrement plus complexe en raison même de la superposition, de la combinaison des modes de production d’une part, des modes de consommation d’autre part. Il fait pièce à la vieille conception marxiste selon laquelle c’est la praxis (l’ensemble des activités humaines), qui détermine les superstructures idéologiques, c’est-à-dire les visions du monde. Mais l’inverse n’en est pas moins faux: l’idéologie selon laquelle il suffirait de « changer les mentalités » vient buter contre des usages et contre la survivance d’objets, qui, à l’image de l’American Motors, possèdent une certaine valeur socio-symbolique. C’est en ce sens que je propose de lire le mot « reflux » qui coiffe l’installation. L’idée même de table rase est une utopie, et l’installation de Stéphane Cauchy ne suggérait pas autre chose en mettant en évidence la cohabitation, l’emboîtement plus ou moins heureux d’objets ayant un vécu.

C’est également l’une des voies sur lesquelles nous mène Djos Janssens qui a planté, devant le château de Beerlegem, un panneau publicitaire annonçant la construction prochaine, dans le parc du château, d’un chalet de montagne proposé à la vente. Dans la commune de Bastogne, un projet similaire avait déjà scandalisé ceux qui l’avaient pris au sérieux. Il n’est pas difficile d’imaginer un accueil semblable à Zwalm, puisque Djos Janssens connaît parfaitement la structure de nos représentations. Son chalet suisse s’oppose en effet au château en symbolisant le « moderne » par rapport à « l’ancien », le « global » et « l’impersonnel » par rapport au « caractère local ». Or, si l’on se penche sur l’histoire du château de Beerlegem, on s’aperçoit très vite que ces notions sont toutes relatives. Edifié dans la première moitié du XVIIIe siècle dans un style classique teinté d’influences françaises, il a été complètement restructuré en 1872 et adapté au style néoclassique. Certains éléments témoignent également d’une assimilation du rococo français. Le château n’est donc pas caractéristique d’une époque, pas plus qu’il n’est représentatif d’un style « local ». C’est ce que l’on pourrait appeler, métaphoriquement, un composite, formé de matériaux hétérogènes accumulés au cours du temps et articulés dans un même objet (caractère qui le rapproche des assemblages de Stéphane Cauchy et d’Arnaud Verley & Philémon). Pourtant, ce que souligne Djos Janssens dans son installation, c’est que nos représentations ignorent cette complexité et se contentent d’opposer « local » et « global », « ancien » et « nouveau ». Le choix de l’artiste d’avoir utilisé sur son panneau l’ancien sigle de la Communauté économique européenne (CEE) prend alors tout son sens. L’Union européenne actuelle est, par excellence, le produit d’une histoire complexe et d’un empilement de structures que nos représentations ignorent en la réduisant à une macro-organisation « abstraite » et « globale » s’opposant à ce qui est perçu comme le « concret », le « local ».

S’il fallait déterminer le sujet des œuvres rencontrées jusqu’ici (et qui n’est ni la nature ni le paysage, comme on a pu le constater) je dirais que chacune s’intéresse, selon un angle de vue qui lui est propre, aux cadres normatifs – matériels ou mentaux – qui sous-tendent nos représentations et notre organisation du monde. Celles dont je voudrais parler maintenant abordent, là encore avec des sensibilités différentes, la question de la connaissance.

La comparaison avec l’observatoire me paraît un outil intéressant pour appréhender la structure en bois que Jo Lathwood a fabriquée dans un champ vierge s’étendant à perte de vue. Un observatoire est en effet un lieu spécialisé depuis lequel on examine un objet précis. En astronomie par exemple, il abrite les instruments d’observation du ciel (télescopes, etc.). On parle également d’observatoires pour désigner des organismes chargés d’ausculter un objet du monde social: observatoire des politiques culturelles, des médias ou encore des retraites. L’observatoire de Jo Lathwood est percé non pas d’un, mais de cinq orifices, multipliant ainsi les points de vue. Pourtant, seul l’orifice central montre effectivement ce qui se trouve dans son champ. Grâce à un système de miroirs, les autres donnent sur le ciel, sur le sol ou sur une partie du paysage différente de celle à laquelle l’observateur s’attend. Ce que soulignent ces miroirs qui dévient notre regard, c’est qu’à partir du moment où l’on décide d’abandonner la focalisation unique, on prend conscience de ce qui se trouve hors-champ. Plus les points de vue s’additionnent, plus on réalise combien la décision est arbitraire. On prend aussi conscience du fait qu’on pourrait ainsi multiplier les angles de vue à l’infini. Il est souvent plus confortable de se contenter d’une focalisation unique, surtout lorsque celle-ci fait apparaître, comme l’orifice central dans l’installation de Jo Lathwood, une ligne d’horizon parfaitement droite, c’est-à-dire une portion de réel sélectionnée parce qu’elle satisfait l’esprit. L’arbitraire de la décision est d’ailleurs mis en évidence par l’emploi du cercle – forme géométrique parfaite – pour les orifices. L’intérêt du travail de Jo Lathwood est à mon avis de montrer que nous continuons à privilégier la focalisation unique alors même que nous savons que celle-ci repose sur une illusion. L’artiste a en effet pris le soin d’exhiber les miroirs qui se trouvent derrière les cercles latéraux et présente ce choix comme une volonté de mettre d’emblée le spectateur face à la supercherie qui sous-tend le mécanisme. En d’autres termes, créer un observatoire pour chaque objet ou pour chaque problème de la vie sociale, comme nous le faisons actuellement, revient à extraire artificiellement cet objet ou problème de son environnement, et ce en connaissance de cause. Le cadrage s’en trouve si resserré qu’il finit effectivement par faire émerger une représentation simpliste, donc commode, du réel; c’est bien ce que suggère la ligne droite dans le cercle central. Le deuxième point à prendre en compte est le fait qu’en principe, un observatoire permet de voir sans être vu (pensons à l’observatoire militaire ou à l’observatoire de la nature qui camoufle l’observateur pour ne pas effrayer les oiseaux). Faire aujourd’hui usage de l’observatoire revient donc aussi à dissimuler le point de vue à l’origine de la modélisation du sujet étudié. Face à l’installation, on peut s’interroger quant à la pérennité de

cette mécanique jusqu’ici bien huilée, l’artiste ayant multiplié, dans sa cabane de bois, les interstices révélant la présence de l’observateur. Le titre de l’œuvre, As far as I can see, peut ainsi être interprété de deux manières. Au sens propre il signifie « aussi loin que mes yeux me permettent de voir ». Mais au sens figuré l’idée exprimée devient: « pour autant que je puisse en juger », c’est-à-dire « pour autant que mon hyperspécialisation dans un domaine me permette d’en juger ».

Goele De Bruyn a traité de manière très poétique cette même question. Sa sphère de bronze abrite une lampe; elle est aussi criblée de petits trous que l’artiste a placés en observant une photographie de la face cachée de la Lune, celle qui est invisible depuis la Terre. Plus le visiteur s’approche de cette lune de bronze, plus l’intensité de la lumière faiblit. Le processus devient intéressant si l’on songe au fait qu’en 1968, pour pouvoir observer directement la face obscure de la Lune, les astronautes ont dû en faire le tour, et donc renoncer à la lumière du Soleil… Ce que ce rapprochement suggère, c’est qu’en accédant à la connaissance, l’homme a dû renoncer à l’éblouissement, c’est-à-dire, au sens propre, à la lumière solaire, et, métaphoriquement, au pouvoir de fascination que les astres ont exercé sur lui pendant des siècles. Car si, de loin, la lune de Goele De Bruyn apparaît comme une véritable boule de feu éclatante, poétique et mystérieuse, à l’image de la Lune ou du Soleil observés depuis la Terre, de près en revanche, c’est un objet terne exhibant sa structure et ses entrailles. Plus on s’en approche, plus le mystère se dissipe: c’est en effet la curiosité et la volonté d’accéder à une connaissance chirurgicale de la Lune qui ont privé l’astre de son pouvoir d’enchantement. Goele De Bruyn insiste sur le fait que sa lune ne devait pas ressembler à un lustre et être perçue comme un objet de décoration. De près, on s’aperçoit qu’elle l’a sectionnée sur un côté, reproduisant les coupes transversales qui illustrent les manuels de science. Elle a également laissé une partie des évents qui ont permis de couler le bronze dans le moule, révélant ainsi le processus de fabrication de l’œuvre. L’objet, énigmatique au premier abord, a donc livré tous ses secrets; il n’en reste qu’une carcasse éteinte. Notons que les évents ressemblent aux branches des arbres formant une voûte autour de l’installation, mais là encore, cette similitude ne fait que rappeler qu’ils sont la trace figée du passage du bronze dans un objet à présent pétrifié quand la sève, elle, diffuse la vie dans les branches. En s’approchant des astres, l’homme ne s’est pas brûlé les ailes, mais le désenchantement est peut-être un châtiment plus terrible que la mort d’Icare.

En ayant ainsi invité à s’aventurer dans l’observation de quelques-unes des œuvres de cette édition, j’espère avoir convaincu que leurs enjeux allaient bien au-delà de la simple volonté de « sortir l’art » des musées ou « d’investir la nature ». Il me semble urgent de revoir nos critères d’appréhension des manifestations telles que Kunst&Zwalm. L’utilisation de plus en plus répandue d’expressions telles que « art écologique » ou « art environnemental » me paraît redoutable dans la mesure où, d’une part, elle réduit l’art à la simple question du lieu et, d’autre part, l’instrumentalise. Car s’il est un reproche que l’on peut faire aux catégories d’appréciation que je dénonce, c’est bien celui-ci: elles nous dispensent de l’effort – mais nous ôtent aussi le plaisir – de regarder vraiment ce que nous avons sous les yeux.

L’utilisation de la locution latine in situ pour désigner les œuvres exposées dans la nature me semble aussi problématique dans la mesure où elle repose sur l’idée que celles-ci, plus que d’autres, prendraient en compte le lieu où elles sont installées. Or, quelle que soit l’époque à laquelle elles appartiennent, toutes les œuvres ont un lieu. Le fait qu’elles aient été destinées à être vues de près ou de loin, à être exposées en hauteur ou à même le sol, dans une église à peine éclairée ou dans un palais vénitien est déterminant pour comprendre leurs conditions de production et de réception et donc pour s’engager dans leur interprétation. L’espace « neutre » de la galerie est aussi un lieu, et y exposer est loin d’être anodin. En d’autres termes, c’est bien à l’articulation entre l’œuvre et son lieu qu’il faut réfléchir. Ce dernier n’est pas en soi porteur de sens; c’est sur la manière avec laquelle l’œuvre le travaille qu’il faut s’interroger. Ce qui ne peut se faire sans une observation attentive de celle-ci.

Bénédicte Duvernay

septembre 2011

1 Kirk Varnedoe, Pictures of nothing: Abstract art since Pollock, Princeton University Press, 2006.

2 Jean Zammit, Pratiques mortuaires et traitement du cadavre ancien (plaidoyer pour une nécro-archéologie), in Revue archéologique de Picardie, Numéro spécial 21, 2003, pp. 185-194.

3 Daniel Ligou, L’Evolution des cimetières, in Archives des sciences sociales des religions, N. 39, 1975, pp. 61-77.

But by retaining only the lowest common denominator for these otherwise very diverse works of art, there is hardly anything else left to say about them, except that ‘they have taken art out of the official art circuit’, ‘they have developed a philosophy of space’, or that ‘they have turned the landscape itself into the object of art’ – comments that are often voiced.

Yet I believe that what underlies these interpretations is a mix-up of subject and medium. In a particularly accurate analysis of Double Negative1, art historian Kirk Varnedoe points out that there a contrast between the public’s perception of the work from below – i.e. when we experience the work inside the trenches – and our perception of it from above, for example when we look at an aerial photograph of the trenches. Looking from inside the trenches, we see the rugged structure of sedimentary rock, which was formed by the accumulation of countless strata. We see a dense millefeuille, which in archaeological terms represents the slowness of geological time and of the development of humankind. The aerial photograph on the other hand highlights a pure, simple form – two trenches that cut through the earth – as well as the force and the brutality of the human intervention (more than 200,000 tons of rock have been dug out to create the trenches). From this point of view, we have to conclude that the creation of a simple shape has involved the rapid and irreparable destruction of a complex structure that itself was the result of an extremely long natural process. Furthermore, if we take into account the fact that the contrast between the aerial view and the ground view corresponds to a contrast between a collective and an individual experience, the anthropological implications of Double Negative become even more evident. Varnedoe took a particular interest in the history of aerial views. He rightly observed that for example the photograph László Moholy-Nagy took in 1928 standing on top of the tower of the radio broadcasting station in Berllin, presents a type of view that radiates an optimism that has to do with the possibility to observe the world from a new viewpoint – a viewpoint that is supposed to be more objective. Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty or Heizer’s work, by contrast, are more related to the geoglyphs in the Nazca desert and express a certain pessimism with regard to the future of humankind in the nuclear age. This type of preoccupation is evident for the first time in Isamu Noguchi’s huge project for a ‘sculpture that can be seen from Mars’ – a project that originated shortly after the use of the first atomic bombs (1947).

The work of Smithson, Heizer and Richard Long should also be confronted with works that belong to the preceding era. Early in the 1960s there was a first generation of minimalists – including Donald Judd, Carl Andre, etc – that mainly used simple, neutral, pragmatic shapes, which inside the art gallery only referred to the experience of the present. Varnedoe notes that at the end of the 1960s, the formal vocabulary of the minimalists was recycled by various artists who started to use a different scale and who adapted this vocabulary to entirely different spaces, precisely to provide an answer to new artistic preoccupations.

Working with desert landscapes was therefore not a goal in itself for these artists. Rather, it was a means to express new challenges, as well as their preoccupation with the long term future of our civilization – a preoccupation that was absent from the positive pragmatism that prevailed in the preceding period. Viewed from this perspective, we are far removed from the idea that ‘art must be taken out of the museum’. In order to understand these works of art, we therefore need to look beyond the question of their location. The fact that art leaves the traditional exhibition spaces and heads for virgin territories transcends the simple need to push back the frontiers of art. Nature is not the subject of these works, but the medium that allows the artist to lend a new meaning to the minimalist language. Working in nature is different from making works about nature.

If I have made a detour, it is because it seemed prerequisite to me to make it clear that is equally wrong to consider the works of art at the present exhibition a priori in terms of the artist ‘appropriating the landscape’, or to refer in this context to ‘the integration of the natural and social environment’, and the like. Such interpretations reduce the works of art to the mere satisfying of a social need. I hope a mutual confrontation of the works will make it clear that more interesting themes play a part.

Nicolas Durand’s work for example is not a poetic invitation to contemplate the surrounding countryside. Yet it is tempting to lie down on the two stone loungers he has installed beside the tombstones at the churchyard in Paulatem.

Before we continue I propose that we halt for a moment to reflect on the question what a cemetery or a graveyard actually is, departing from the installation Wim Cuyvers created for the 2007 edition of Kunst&Zwalm. At a churchyard in the region Cuyvers installed camping tents between the tombstones, an intervention that met with a quite hostile response from the local inhabitants. The reason becomes obvious, if we take into account the fact that a tent relates to ephemeral things, to a nomadic lifestyle, to the movement that is inherent to life – concepts that are at odds with the view of death in Western, Christian societies. In these, death is associated with an ‘eternal resting place’, that is entirely unrelated to the infamous earthly existence.

However, this is only one of the possible representations of death. Some societies for example think that the body of the deceased should be returned to ‘mother nature’ and therefore it should be left alone. Other societies use the bones of their dead to make weapons or ornaments. The Buddhists in Tibet and Nepal cut the body into pieces, which are exposed in the open for birds to feed on.2 Thus in countless societies the human body plays a part in the cycle of life. However, that is not case in Christian societies, where the border between life and death is as it where more hermetically sealed. In Christian societies the age-old practice of burying the body is based on the belief in the resurrection of the flesh. The early Christian rulers put much effort in banning cremation, precisely because the body was thought to ‘rise gloriously’ after death. This preoccupation with safeguarding the body also explains why since the early Middle Ages burial grounds found a place next to the church – they became churchyards. I believe that in our societies we distinguish between the visible, earthly, ephemeral body and the mortal remains of it, which accommodates the soul and which is buried and thus protected, as it awaits eternal life. In my view, this divide is precisely suggested by on the one hand moving the loungers to the churchyard and on the other hand by using stone for it – a durable material, unlike the plastic that is usually used for garden furniture (plastic is a material for disposable items and is of hardly any value). The fact that Durand conceived his installation after he had seen several pairs of loungers in the Zwalm region, prompts us to pay attention to another aspect of his work.

Let us therefore look at the installation in its context, i.e. we consider church + churchyard + tombstones. This context makes us think of the houses around, which are surrounded by a fenced garden with loungers that look out on the most pleasant part of the landscape. The church of Paulatem is in fact a house – which has been reconstructed with bricks for that matter – surrounded by an enclosed green terrain. The tombs are parallel to each other and are also oriented towards the countryside. We cannot help but being struck by the analogy.

Furthermore, I would like to draw attention to the euphemistic phrase ‘final resting place’, a term that is sometimes used to refer to a cemetery or churchyard, and to the image we have just evoked of the church as a place where the dead are protected. And there is also the word ‘cemetery’, which also exists in Romance and Slavic languages and which is derived from the Latin coemeterium, which itself was derived from the Greek κοιμασθαι, which means ‘to sleep’.3 Finally, I also want to point to the fact that, just like people have their own lounger in their garden, each individual person is allotted his or her proper grave – in the West, both life and death are a matter for individuals. The configuration of the tombstones is therefore subject to the same rules that govern the distance between living beings. Thus we conclude that in our society life and death are strictly separated, but paradoxically both are governed by the same rules. Our tombstones are all based on a single model, but what about the entirely identical loungers and the gardens where we find these? The gardens are surrounded by a fence that protects the house and separates it form the neighbour’s, which is nonetheless similar. Perhaps the wall around the garden is intended to achieve the same goal as the wall around the churchyard, i.e. locking out those who do not belong there. Indeed the low wall around the churchyard reminds us of the fact that for a long time people had to have died in communion with the Church in order to enjoy the privilege of being buried on the churchyard. Once more this emphasizes the similarity between the tombstone and the lounger: both have to provide a frame for the body – i.e. life and death are subjected to a same system of rules. Durand’s work therefore is anything but an invitation to contemplate the landscape. Rather, it invites us to reflect on the way we organize our living space (and the space for death, which amounts to the same thing). And that, in my view, is quite more interesting.

Adriaan Verwée’s oeuvre, on the contrary, does not represent anything. Rather, it is on a meaning level that Verwée and Durand meet.

On a sort of scaffold or ‘pontoon’ at the edge of a forest, the artist has created an installation comprising several elements: a structure made of perpendicular metal bars; in the back rectangular plasterboards are piled up; in front of this fragile installation, there is a pile of pieces of plasterboard – fragments of the same plasterboards that are piled up in the back, with several right angles visible. We are thus confronted with three types of assemblages. The parts of the metal structure have been welded together. The components of the plasterboard construction all rest on each other. The scraps of plasterboard are simply piled up on the ground. But this haphazard pile is doubtlessly the least fragile of the three, though its stability is only assured by the law of gravity. It suffices to have a glance at the first two elements to notice their vulnerability. Bad weather will be enough to knock them over. Paradoxically, the most stable structure is the pile that has collapsed. Yet it represents that which did not hold out, failure, the waste matter of a society that prefers orderly, controlled constructions – such as the assemblage of perpendicular plasterboards under which Verwée has carefully hidden measuring tools. The artist has also laid three square panes of glass and several metal bars on the plasterboards, which according to the artist represent ‘the workbench of a picture framer’, i.e. of a man whose job it is to place objects in an orthonormal frame. Compared with the construction of plasterboards, the haphazard pile of scraps of plasterboard represents that which eludes the standard and which we usually prefer to hide, for example with a tarpaulin – and that is precisely what the artist has hung from the branches of a tree next to the installation. It is as if he wants to emphasize the heap of scrap through the tarpaulin, and as if he wants to reminds us that to create an orderly form, some cutting is required, which necessarily results in waste material.