Of: de kousenfabriek van Rousseau. Enkele overpeinzingen van een tegendraadse wandelaar.

I. Fietsroute * (een inleiding)

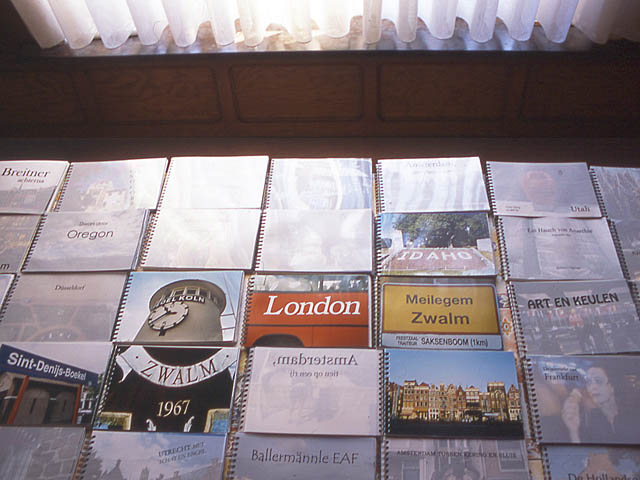

Deze tekst is GEEN toelichting bij een tentoonstelling. De vierde editie van Kunst & Zwalm was immers meer dan welsprekend. Elke interpreterende publicatie over de exposanten en het getoonde werk zou afbreuk doen aan de persoonlijke herinneringen van de bezoeker en dus aan het project. Anderzijds kan dit essay wel gelezen worden als een context, als een geschreven wandeling ROND de tentoonstelling. Daarbij heeft de bezoeker-schrijver-wandelaar het geplande parcours verlaten, en zwerft hij ergens rond tussen koeien, brandnetels en struikgewas. In die zin vormt de resulterende tekst geen recensie (in de zin van een reductie), maar een expansie van het tentoonstellingsproject Kunst & Zwalm 2003. Aangrijppunten zijn het bezoek aan de tentoonstelling en de lectuur van enkele teksten. Beide komen samen in een aantal kritische overpeinzingen van een tegendraadse wandelaar, een titel die uiteraard refereert aan Jean-Jacques Rousseau's laatste (en onvoltooid gebleven) autobiografische geschrift , 'Overpeinzingen van een eenzame wandelaar', posthuum gepubliceerd in 1782. In de vorm van tien 'wandelingen' (promenades) blikt de bejaarde filosoof daarin terug op zijn leven.

Daarbij legt hij een ontwapenende eerlijkheid aan de dag en stopt hij mislukkingen en teleurstellingen niet onder stoelen of banken. Tijdens dit proces van intro- en retrospectie vormt zijn beweging door en de beschouwing van het landschap een rode draad. Wandeling en mijmering sturen en beïnvloeden elkaar. In de promenade komen het fysieke en het mentale tot een efficiënte synthese. De invloed van Rousseau's gedachtengoed op de romantiek is dan ook aanzienlijk. Diverse symptomen van het romantische, zoals de sentimentele poëzie, de autobiografie, de briefroman, het pittoreske landschapsschilderij en de landschapstuin kunnen aan Rousseau's publicaties gekoppeld worden. Het bindend element tussen deze verschillende genres is net de wandeling.

In die zin is Kunst & Zwalm een romantisch project. De wandeling, het kunstwerk en het landschap zijn er namelijk nauw met elkaar verbonden. Deze verbinding vormt de rode draad doorheen de vier edities, samen met het principe dat een aantal Vlaamse of Belgische kunstenaars geconfonteerd worden met enkele kunstenaars uit een welbepaald 'gastland' (Nederland, Frankrijk en nu Catalonië). Wanneer men dit alles overweegt, lijkt het alsof in het concept van Kunst & Zwalm een aantal potentiële spanningen ingebakken zitten, met name het conflict tussen cultuur en natuur, en de culturele differentiatie tussen nationale identiteiten. In de tentoonstelling worden deze potentiële conflicten echter uitgesteld of zelfs geneutraliseerd door de humanistische mythe van het kunstwerk. De kunst vormt in deze de verzoenende of verbindende factor tussen bio-ecologische en socio-culturele verschillen.Land en Landschap, de twee parameters waarmee Kunst & Zwalm zich profileert, zijn bij nader inzien echter alles behalve onschuldige concepten. Net als het concept 'kunst' zijn 'land' en 'landschap' loodzware ideologische constructies.

Zo kan een eenvoudige vraag naar het 'land' van herkomst tal van socio-politieke bedenkingen genereren.Zijn de deelnemende kunstenaars van de laatste editie bijvoorbeeld Vlamingen en Catalanen, of zijn het Belgen en Spanjaarden?

Alleen al deze (retorische) vraagstelling expliciteert een aantal latente ideologische spanningsvelden waaruit blijkt dat land en nationaliteit ver van 'onschuldige' gegevens zijn.

II. Duurzaam toerisme (landschap en vrije tijd)

Beide concepten, Land en Landschap, stammen in grote mate uit de romantiek.

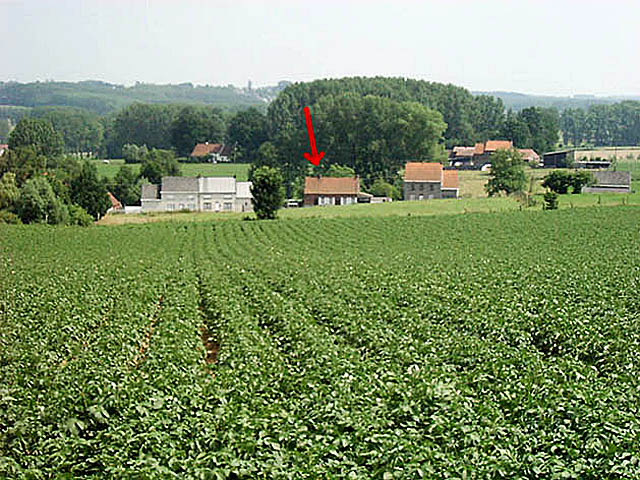

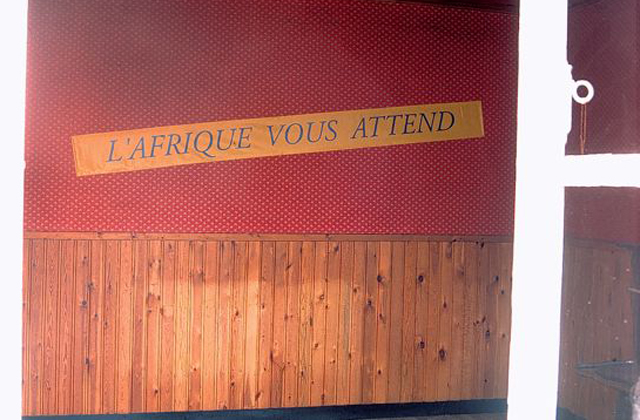

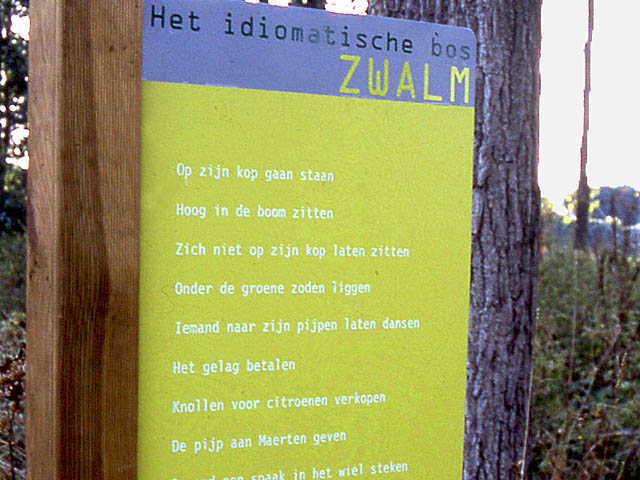

Beide bekleden een fundamentele plaats in het zelfbeeld van de 19de eeuwse burger en vormen een sleutel tot zijn relaties met het verleden (het land) en de natuur (het landschap). Waar het 'land' in de eerste plaats een politieke fictie is, en een metafoor van de spanningen tussen het collectieve en het indviduele, is het 'landschap' een ecologische fictie, die een aantal andere, misschien meer fundamentele conflicten verdoezelt. Zo kan het landschap doorheen de eeuwen gelezen worden als het slagveld waar de belangen van de mens domineren op de wetmatigheden van de natuur. Het landschap is ingekaderde, uitgezuiverde en dus geconstrueerde natuur. Maar tegelijkertijd wordt het landschap in kunst en cultuur voortdurend ingeschakeld voor de radicale ontkenning van deze manipulatie. Die mythe van het ongerepte platteland is ondertussen eeuwenoud en ontwikkelt zich van de bucolische poëzie van Vergilius over de heimatschilderijen van de Vlaamse expressionisten tot het TV-programma 'Vlaanderen Vakantieland'. Ook in Variant, het 'Vlaamse-Ardennen.be Magazine', dat in zijn eerste nummer ondermeer aandacht besteedt aan Kunst & Zwalm, voeren fraaie kleurenfoto's van idyllische landschappen de hoofdtoon. Fietsroutes, streekgerechten, pickickplekjes én tentoonstellingstrajecten moeten de vermoeide stedeling naar deze idyllische contreien lokken. Dit 'regionaal vrijetijdsmagazine' is een uitstekend voorbeeld van hoe natuur en kunst vandaag in grote mate gereduceerd zijn tot vrijetijdsfenomenen. Deze reductie resulteert echter zowel in een idealisering als in een potentiële bedreiging. De in de massamedia opgevoerde fictie van het ongerepte, idyllische landschap trekt immers horden stedelingen aan die op hun beurt de idylle onder druk zetten en aantasten.

In het hedendaagse landschap gaan constructie en destructie hand in hand.

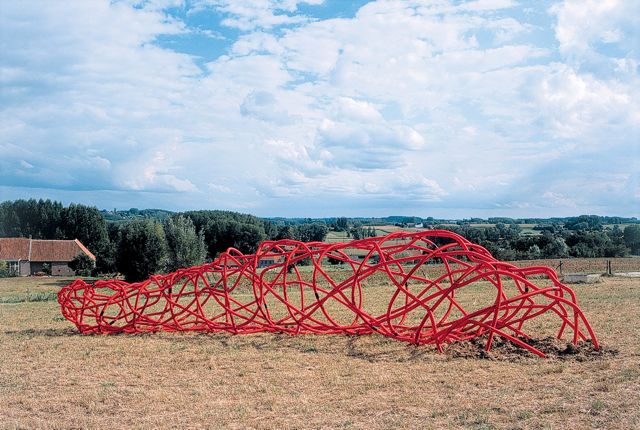

Dit proces werd reeds in 1968 beschreven door architect Renaat Braem: 'Wonen we in de ontzaglijke huizenkoek, dan hebben we de auto nodig om 's zaterdags en 's zondags naar de zgn. vrije natuur te ontvluchten. Ofwel gaan we in die vrije natuur wonen, om ze zo allengs te vernietigen.' ('Het lelijkste land ter wereld'). Het 'landschap' verliest zijn onschuld en geeft zich pas bloot als ideologische constructie wanneer men oog krijgt voor dat wat weggelaten is (industrie, pollutie, urbanisatie, verkeersfiles, koelboxtoerisme, kriminaliteit). Via deze eliminatie profileert het nostalgische landschap zich als tegenpool van de harde urbane realiteit. Kunstwerken kunnen zich laten inschakelen in deze confictverdoezelende benaderingen door te collaboreren aan deze camouflagetactieken. OF ze kunnen in bepaalde gevallen functioneren als potentiële stoorzenders die ideologische concepten als land en landschap in een minder vanzelfsprekende context belichten en daardoor deconstrueren. Tentoonstellingsprojecten als Kunst & Zwalm zijn daar, door hun daarnet geschetste specificiteit, in principe geschikte momenten voor. Omdat kunst, land en landschap er een tijdelijke verbintenis aangaan, ontwikkelt zich een potentiëel netwerk van betekenissen. Men kan de gesponnen lijnen van dit netwerk volgen, of men kan er tegen in gaan. En dat brengt ons weer bij de wandeling.

III. Leuke picknickplekjes (een Rousseauaans intermezzo)

Ik was alleen en drong diep door in de kloven van de berg, en gaande van het ene bos naar het andere en van ene rots naar de volgende kwam ik op een open plek die zo verborgen was dat ik mijn leven lang niets wilders heb gezien. Zwarte sparren en enorme beuken, waarvan er verschillende omgevallen waren van ouderdom en in elkaar waren verstrengeld, sloten als een ondoordringbare versperring deze plaats af. Enkele openingen in die sombere omheining gaven slechts loodrecht naar beneden lopende rotsen en ijzingwekkende afgronden te zien, waarin ik alleen durfde te kijken als ik op mijn buik ging liggen. Ransuil, steenuil en kerkuil lieten in de kloven van de berg hun roep horen, enkele schaarse maar vertrouwde kleinere vogels temperden intussen het huiveringwekkende karakter van dit verlaten oord. Daar vond ik Dentaria heptaphyllos, Cysclamen, het vogelnestje, de grote Lacerpitium en enkele andere planten die mij boeiden en lange tijd aangenaam bezig hielden. Maar ongemerkt overweldigd door de sterke indruk die de dingen op mij maakten, vergat ik botanie en planten, ging zitten op kussens van Lycopodium en mos en begon meer op mijn gemak te dromen, terwijl ik bedacht dat ik mij daar in een schuilplaats bevond die op de hele wereld onbekend was en waar mijn vervolgers mij niet zouden ontdekken. Een gevoel van trots mengde zich weldra in deze overpeinzing. Ik vergeleek mezelf met de grote reizigers die een onbewoond eiland ontdekken en tevreden dacht ik: ongetwijfeld ben ik de eerste mens die tot hier is doorgedrongen. Ik beschouwde mezelf bijna als een tweede Columbus.

Terwijl ik bij deze gedachte groeide van trots hoorde ik niet ver van mij vandaan een bepaald geratel dat ik meende te herkennen. Ik luisterde, hetzelfde geluid herhaalde zich en werd krachtiger. Verbaasd en nieuwsgierig stond ik op, baande mij een weg door het dichte struikgewas in de richting waar het geluid vandaan kwam en in een dal op twintig passen van de plek waar ik dacht als eerste gekomen te zijn, zag ik een kousenfabriek.

Deze anecdote uit Rousseau's zevende wandeling is niet alleen geestig maar ook bijzonder actueel. De filosoof lijkt hier zelf de spot te drijven met zijn eigen idealistische natuurverheerlijking en lijkt daarbij te suggeren dat de ongerepte natuur, een van de basisconcepten van de Rouseauaanse romantiek, een mythe is. In deze tegendraadse anecdote kantelt de romantiek in haar tegenpool, het realisme. Door de ontnuchterende anticlimax van de kousenfabriek deconstrueert Rousseau immers het door hem zelf geweven natuurbeeld. Het tijdens een promenade 'ontdekte' idyllische plekje, wordt, door de promenade nog enkele stappen verder te zetten, in één oogopslag herleid tot de achtertuin van een fabriek. Het is het herkenbare gevoel van ontluistering dat we allemaal wel eens ervaren hebben toen we tijdens een 'natuurwandeling' op een sluikstort stootten.

Dit ontluisterende, onomkeerbare, maar kritische inzicht kan echter enkel bereikt worden door middel van de wandeling. Wie wandelt, beweegt doorheen contexten. En dit zowel fysiek als mentaal. Terwijl Rousseau wandelt, overpeinst hij zijn leven. Zijn voortbewegen in de ruimte gaat gepaard met een terugbeweging in de tijd. Zijn wandeling wordt daardoor tegendraads. Ze leidt tot ontnuchterende inzichten.

In die zin is de wandeling (de promenade) het tegendeel van het parcours, het aangelegde of voorgekauwde traject. (zie hierover ook m'n essay 'Spoils of the Park. Het park als bezet gebied', in: 'Zoersel 2002. Een raadsel voor Zoersel', 2002) Een wandelaar is immers een migrant. Hij onttrekt zich aan vastgelegde en opgelegde structuren en verlaat zelfs de platgetreden paden. Hij is de bewegende buitenstaander. Wie zich verplaatst is namelijk ongrijpbaar. Vandaar ook de negatieve politieke connotaties van woorden als migrant,vluchteling, allochtoon, asielzoeker en zigeuner. Door zich te verplaatsen bevindt de nomade zich immers in een machtsvacuüm en roept hij angst en agressie op bij de sedentaire, autochtone bevolking. Die andere grote theoreticus van de wandeling, de filosoof Ton Lemaire, omschrijft de wandeling dan ook als de 'praktijk van de ruimte', in tegenstelling tot het uitzicht dat in zijn ogen een 'theorie van de ruimte is'('Filosofie van het landschap', 1970) In die zin kan de wandeling beschouwd worden als een vorm van toegepaste ecologie.

Na zijn dood wordt de figuur van Jean-Jacques Rousseau opgeblazen tot mythische proporties. Van de wandeling als reflexieve en kritische handeling is in de romantische recuperatie van Rousseau echter nog weinig te merken. Een treffend voorbeeld van de romantische Rousseau-verheerlijking en -recuperatie is 'Voyage à Ermenonville' van Arsenne Thiébaut-de- Berneaud, gepubliceerd in 1819. Dit curieuse boek, onderverdeeld in acht 'promenades' vormt, zoals de ondertitel 'Contenant des Anecdotes inédites sur J.J. Rousseau, le plan des jardins, et la flore d'Ermenonville publiée pur la première fois' ons vertelt, een 'geleerde', maar tegelijk 'sentimentele' reisgids naar en in het landgoed van Ermenonville, waar Rousseau zijn laatste levensjaren had doorgebracht en waar zijn laatste rustplaats zich bevindt. Na zijn overlijden wordt het park, dat naar de Engelse mode aangelegd was als een pittoreske landschapstuin, een waar bedevaartsoord voor Rousseaulievende romantici. Het boek van Thiébaut-de-Berneaud speelt handig in op de Rousseau-mythe en bevat een volledige lijst van de aanwezige flora, een beschrijving van het traject Parijs-Ermenonville, aanwijzingen voor de aanleg van een herbarium, een gedetailleerde beschrijving van het landschapspark, enkele pagina's toepasselijke bladmuziek, en een hoop literaire en filosofische anecdotes. De bijgevoegde plattegrond van het park, waarop alle bezienwaardigheden aangeduid staan, laat zich haast lezen als die van een romantisch pretpark. Van Rousseau's revelerende kousenfabriek is uiteraard geen sprake. Wel van bronnen, grotten, cenotaven, eilanden, graftombes, filosofische tempels, kluizenaarshutten, molens en populieren. Rousseau's eigenzinnige en subversieve promenade is hier verworden tot een toeristisch parcours voorzien van voorgeschreven en voorgekauwde ervaringen.

IV. Lekker uit eigen streek (Long vs. Smithson)

De wandeling heeft nochtans, zoals we reeds eerder vaststelden, wel degelijk een kritisch potentiëel. Het hoeft dan ook niet te verbazen dat de avant-gardes van de twintigste eeuw de wandeling hanteerden als subversieve strategie. Maar de manieren waarop in de kunst gewandeld wordt, reveleren veel over de atttide van de kunstenaar ten opzichte van zijn omgeving. In het midden van de jaren 1960 laat de Nederlandse kunstenaar Stanley Brouwn zich als een verdwaalde stadstoerist door voorbijgangers de weg tot een bepaalde plaats uittekenen en exposeert de schetsen later onder de noemer 'This way Brouwn'.De Amerikaanse performance-kunstenaar Vito Acconci persifleert dan weer de 19de eeuwse stadsflaneur in zijn 'following pieces' van de late jaren 1960, waarbij hij zich tot doel stelt een onbekende te achtervolgen tot op het moment dat die een huis in gaat. (Op haar beurt laat de Franse kunstenares Sophie Calle zich jaren later een tijd lang schaduwen door een professioneel detectivebureau en exposeert zij de resulterende beeld- en tekstdocumenten over haar doen en laten.) Maar het is vooral de 'natuurwandeling' die een aantal kunstenaars in de late jaren 1960 (niet toevallig ook de periode van Renaat Braems eerder geciteerde schotschrift) voorziet van alternatieve ideeën en visies. 'No walk, no work' luidt dan ook het motto van de Britse kunstenaar Hamish Fulton, die samen met Richard Long aan de wieg staat van de Britse land art. 'Ik vond dat de kunst nauwelijks oog had voor de natuurlijke landschappen die deze planeet bedekken, noch gebruik maakte van de ervaringen die deze plaatsen te bieden hadden', noteert Long over het beginmoment van zijn oeuvre. Sindsdien zijn de wandeling en de trektocht zijn artistieke strategieën bij uitstek. Daarbij zoekt hij doorgaans de eenzaamheid op. In zijn sculpturale projecten en fotowerken,waarin de mens schittert door zijn afwezigheid, wordt de kloof tussen stadscultuur en natuur expliciet gevisualiseerd.

Het is opvallend hoe zowel de Britse als de Amerikaanse land art van de jaren omstreeks 1970 symptomen vormen van een neo-romantische verhouding tot het landschap. Tegelijkertijd belichamen de beide tradities echter een radicaal verschillende benadering. Long en Fulton gebruiken het landschap als alternatief voor de stad en visualiseren het in zijn 'pure' staat van maagdelijke natuurlijkheid. Daarbij hanteren zij fototoestel, potlood en papier. Zij nemen de houding aan van een Rousseau die zijn ongerepte plekje ontdekt en tijdelijk in bezit neemt. De mythe van het landschap blijft daarbij in stand gehouden.

De Amerikaanse earth workers (Walter De Maria, Robert Smithson) zijn daarentegen meer gefascineerd door de menselijke sporen in het landschap. Bulldozer en graafmachine worden ingeschakeld in grootscheepse transformaties van het landschap. In hun werk wordt de macht van de mens over de natuur niet gecamoufleerd: zij verkiezen het schokkende zicht op de kousenfabriek. Het landschap wordt fysiek én conceptueel toegetakeld. Vooral Smithson ontpopt zich in zijn earth works en zijn geschriften tot een radicale estheet van het hybride en het onzuivere. Dat komt ondermeer treffend tot uiting in het jaar 1969: terwijl Richard Long een gedocumenteerde trektocht van drie dagen maakt in het landelijke Wiltshire, laat Robert Smithson een vrachtwagenlading asfalt storten in een verlaten steengroeve nabij Rome. In tegenstelling tot Long ziet Smithson de kunst als een mogelijke link tussen ecologie en industrie. 'Ecologie en industrie zijn geen éénrichtingsstraten, eigenlijk zouden ze kruispunten moeten zijn. De kunst kan een hulpbron worden die bemiddelt tussen de ecologist en de industriëel.' Smithsons schitterende beschrijvingen van industriële wastelands doen dan ook in niets onder voor de sublieme landschapsretoriek van de romantiek. Door de erkenning van het hybride en het onzuivere zijn Smithsons wandelingen in wezen tegendraadser dan die van Long. Zij erkennen immers het geconstrueerde, fictieve karakter van het natuurlijke landschap en vormen zo een wapen tegen het ideologische gebruik ervan. In hun respectievelijke omgang met natuur en landschap vertegenwoordigen de Brit Long en de Amerikaan Smithson bij nader inzien een 20ste eeuwse variant van de 19de eeuwse culturele erfenis van hun nationale traditie. Het is de houding van een Constable tegenover die van de Cowboy.

V. De slag bij Gavere (opkomst en ondergang van de wandeltentoonstelling)

Beide kunstenaars, Long én Smithson, zijn in 1971 vertegenwoordigd op een tentoonstelling die de geschiedenis ingaat als de moeder van alle 'wandeltentoonstellingen': Sonsbeek 71. De consequente keuze van de organisatoren en een aantal kunstenaars voor site-specifieke ingrepen maakt deze editie van de Sonsbeek beeldententoonstelling fundamenteel verschillend van de vorige. In plaats van over het Sonsbeekpark te Arnhem, strekt het project zich uit over heel Nederland. Als ondertitel werd dan ook gekozen voor 'Sonsbeek buiten de perken'. De ontwikkeling blijkt zo ingrijpend dat de termen 'manifestatie' en 'activiteit' opduiken in plaats van 'tentoonstelling', en de term 'beeldhouwkunst' voor de gelegenheid vervangen wordt door 'ruimte en ruimtelijke relaties'. De catalogus verschijnt dan ook in twee delen: een met voorstellen en plannen, een later deel met beelden van de realisaties. Sommige kunstenaars realiseren een boek of een film, anderen beperken zich tot een conceptuele bijdrage of een statement in een tijdschrift, een dagblad of de catalogus. Andere kiezen voor radicale ingrepen in het park of het Nederlandse landschap. Richard Long tekent een tijdelijke, witte 'Celtic Sign' in het landschap van Schiermonnikoog. Robert Smithson realiseert een permanente, monumentale 'Spiral Hill' en een 'Broken Circle' in een verlaten zandgroeve te Emmen. De genese en de receptie van Sonsbeek 71 maken ondermeer duidelijk dat dit project enig was in soort, met alle gevolgen vandien. Een aantal projecten werd noodgedwongen niet gerealiseerd. Pers, publiek én politiek reageerden onwennig op de nieuwe format en de nieuwe kunstvormen waaronder land art en concept art. Vanuit de traditionele beroepsverenigingen van beeldende kunstenaars werd er zelfs een heuze hetze tegen het project ontketend. In die zin was de eerste wandeltentoonstelling, zowel artistiek als ecologisch, een subversieve tentoonstelling.

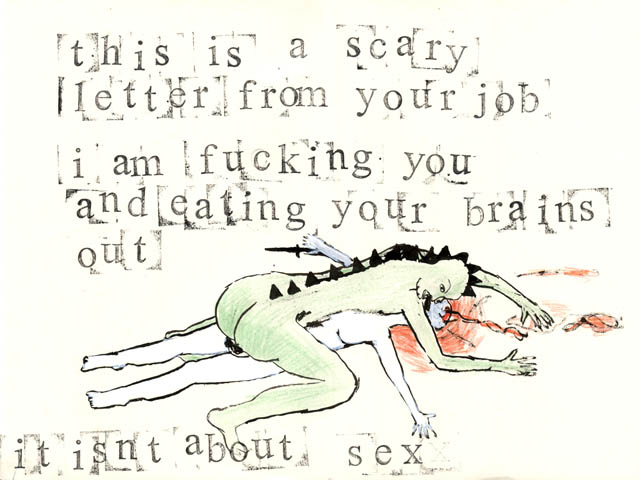

In Sonsbeek 71 wordt de kritische, dynamische activiteit van de nomadische kunstenaar gekopieerd en toegepast op het volledige tentoonstellingsconcept. Het klassieke, museale 'parcours' van de conventionele beeldententoonstelling moet daarbij wijken voor de alternatieve, persoonlijke 'promenade'. Sindsdien zijn park- en stadstentoonstellingen steeds vaker beroep gaan doen op het denk- en benenwerk van de bezoeker: Skulpturprojekte Münster, Chambres d'Amis, Over the Edges en de talrijke kleinere stads, park- en landschapstentoonstellingen die zich vanaf de jaren 1980 ontwikkeld hebben in ondermeer Zoersel, Tielt, Leuven, Watou, Aarschot en Zwalm. Net als de klassieke beeldententoonstelling van weleer (Middelheimbiënnale, Sonsbeek voorafgaand aan 1971) is de wandeltentoonstelling in dat proces een conventie geworden. Vandaag wil elke gemeente of stad haar eigen periodieke 'hedendaagse kunst-project' in de vorm van een biënnale of een triënnale. Kapitaalkrachtige kunstliefhebbers kunnen dan tijdens hun bezoek aan het project iets oppikken van de stad of streek waardoor de lokale middenstand meteen een graantje meepikt van het gebeuren. Maar de organiserende gemeente boekt vooral winst qua symbolisch kapitaal. Hedendaagse kunst roep voor velen nog steeds associaties op met dynamisme, progressiviteit en openheid van geest. In die zin zijn hedendaagse parcourstentoonstellingen vaak blootgesteld aan krachten van politieke en economische recuperatie. Daarbij wordt vakkundig gejongleerd met de democratische mythe van de 'publieke ruimte' en de ecologische mythe van het 'landschap'. Het wandelen heeft daarbij zijn subversieve kracht van reflectie en contextuele kritiek verloren. Het is een vorm van passieve consumptie geworden en is opgenomen in een overkoepelende vrijetijdscultuur. Vandaag zou Rousseau, wanneer hij zijn ongerepte idyllische plekje verlaat, niet oog in oog staan met een kousenfabriek, maar met een kunstwerk .

VI. De ideale combinatie cultuur-natuur (een besluit)

Net zoals de 'experimentele' promenade van Rousseau in de loop van de 19de eeuw een romantische stijlfiguur wordt, ¨heeft de subversieve wandelstrategie van de laatmoderne avant-garde uit de jaren omstreeks 1970 geleid tot het populaire type van de hedendaagse, postmoderne 'wandeltentoonstelling'. In beide historische processen zijn de weerhaken verdwenen, is het product gepolijst. Vandaag blijken wandeltentoonstellingen populairder dan ooit. Ze vormen een niet onbelangrijke factor in de 'ontsluiting' (en de consumptie) van hedendaagse kunst (en van het hedendaagse landelijke). Tegelijkertijd lijkt het radicale, experimentele karakter van deze tentoonstellingsstrategie voorgoed verleden tijd. In het beste geval zorgt de wandeltentoonstelling voor een aangename en toegankelijke manier om hedendaagse kunst te beschouwen. Maar is dat voldoende? Daarom moeten we ons de vraag stellen of kunstwerk en landschap nog gediend zijn met de wandeltentoonstelling. Met andere woorden, geven beide elkaar een fundamentele meerwaarde, of tolereren ze elkaar slechts? Interageren kunstwerk en landschap met elkaar of functioneren ze naast elkaar? Soms lijkt de hedendaagse wandeltentoonstelling op een romantisch gekleurde vlucht uit het museum en (dus) uit de stad. Terwijl deze vlucht in de late jaren 1960, de periode van Long en Smithson, een romantisch-kritische dimensie bezat, lijkt deze dimensie vandaag eerder romantisch-nostalgisch. Terwijl het landschap ten tijde van de land art fungeerde als laboratorium, en de kijker als gemotiveerde participant, lijkt het landschap van nu eerder een pittoresk decor, en de tentoonstellingsbezoeker een streektoerist.

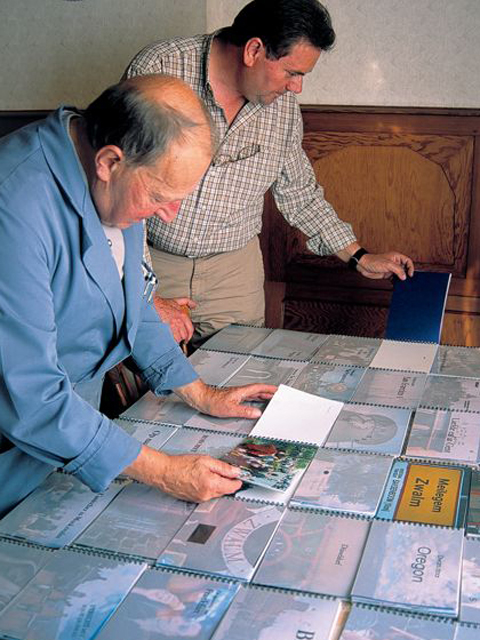

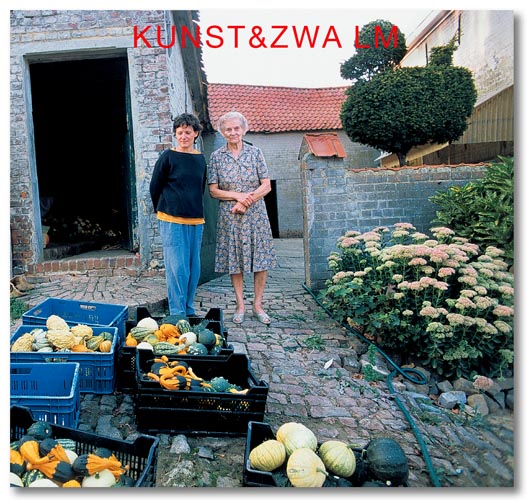

Slechts zelden slagen kunstwerken er vandaag in een meerwaarde aan het landschap te ontlokken, en omgekeerd. Terwijl elk landschap een goudmijn/mijnenveld van betekenissen is, boren kunstwerken vandaag sporadisch de ondergrondse economische, ecologische, sociale en politieke aders aan. Het overaanbod van streek- en parktentoonstellingen zorgt bij een deel van het professionele publiek voor een gevoel van saturatie. Kunstenaars voelen zich op hun beurt haast verplicht aan openluchttentoonstellingen deel te nemen, zelfs al hebben ze weinig of geen affiniteiten of ervaring met site-specifieke of omgevingsgerichte strategieën. Waar de verkenning van het landschap in de late jaren 1960 en de vroege jaren 1970 een radicale, persoonlijke en artistiek beargumenteerde beslissing was, lijkt ze de laatste jaren steeds meer op een extern opgelegde must. Misschien wordt het tijd dat we het vermoeide en overbevraagde landschap even met rust laten en onze kritische aandacht opnieuw richten op het wat verwaarloosde museum. Toch weet het project Kunst & Zwalm enigszins aan de huidige malaise van de postmoderne wandeltentoonstelling te ontsnappen. Dat is te danken aan zijn sociale component. De integratie in en interactie met de lokale gemeenschap verlenen dit project ontegensprekelijk een extra dimensie. Niet zozeer de overbelaste relatie kunstwerk - landschap lijkt me hier essentiëel, dan wel de intense relatie streekbewoner - kunstproject. Dit sociale aspect, het creëren van een lokale betrokkenheid van de bewoners met het initiatief lijkt me dan ook een uitdaging voor andere toekomstige stads- of streektentoonstellingen. Indien dit aspect bij de volgende edities verder uitgediept wordt, kan Kunst & Zwalm hier een experimentele functie hebben. Want zelfs de meest 'eenzame' wandelaar beweegt zich in een sociale context.

Johan Pas, Ekeren, december 2003 (© vzw Boem & Johan Pas)

* Noot: alle ondertitels van dit essay zijn ontleend aan Variant. Vlaamse Ardennen.be Magazine, nr. 1-juli-augustus-september 2003.

Or: the stocking manufactory of Rousseau. Some reflections of a wayward wanderer.

Bicycle route* (an introduction)

This text does not constitute an elucidation of an exhibition. Moreover, the fourth edition of Art & Zwalm was more than evident. Each and every publication about the exhibiting artists or the work they presented would hamper the individual reminiscences of the visitor and hence also this project. On the other hand, this essay could be red as a context, as a written walk AROUND the exhibition. Furthermore, the visitor- author-walker has strayed from the planned roadmap and he hangs about somewhere in between the cows, the stinging nettles and shrubbery. In this sense, the underneath text does not constitute a review (in the sense of a reduction), but much rather an expansion of the exhibition project Art and Zwalm 2003. It is based on a visit to the exhibition as well as the lecture of several texts. Both of these converge in a number of critical reflections of a wayward wanderer, a title which is evidently referring to the last autobiographical writing by Jean-Jacques Rousseau which remains unfinished: 'Reflections of a lonesome wanderer' which was published posthumously in 1782. In the form of ten 'walks' (promenades), the aged philosopher reflects on his life. In the process, he displays a disarming honesty and does not cover up failures and disappointments. This process of intro-and retrospection is based on his moving through and reflections upon the landscape. Walking and reflection guide and influence each other. In these promenades, the physical and mental aspects attain an efficient synthesis. Consequently, the influence of Rousseau's thinking upon Romanticism was considerable. Divergent symptoms of the category of the romantic, such as sentimental poetry, autobiography, the essay in letters, the picturesque landscape painting and the landscape garden can be linked to Rousseau's publication. The connecting element between these divergent genres is the very walk.

In this sense 'Art & Zwalm' are a romantic project. For the walk, the artwork and the landscape are intimately intertwined in it. This connection, as well as the fact that a number of Flemish or Belgian artists are confronted with several artist from a certain 'guest country' (the Netherlands, France and in this case Catalonia) constitutes the greatest common denominator and guiding principle of all four editions. Upon considering the above, it appears that a number of potential tensions are built-in into the concept of 'Art & Zwalm', namely the conflict between culture and nature and the cultural differentiation between divergent national identities. In the exhibition, these potential conflicts are postponed, or rather, they are even neutralized by the humanist myth of the work of art. In this matter, art constitutes the reconciling or linking factor between bio-ecological and social-cultural differences. Upon closer consideration Land and Landscape, these two parameters by means of which 'Art & Zwalm' develops its profile, are anything but innocent concepts. Just like the concept of 'art', those of 'land' and 'landscape' are bathetic ideological constructs.

Consequently, the question of the country of origin, might generate a great many social-political reflections. For instance, are the participating artists of the latest edition Flemish and Catalonian, or are they Belgian and Spaniards? Nothing but a comparable (rhetorical) question like this one makes explicit a few latent ideological fields of tension, revealing land and nationality to be anything but 'innocent' data.

Enduring tourism (landscape and leisure time)

Up to a considerable degree, both concepts, Land and Landscape, are rooted in Romanticism. Both occupy a quintessential position in the self-image of the bourgeois of the 19th century and constitute the key to his relations with the past (the land) and with nature (the landscape). Whereas the 'land' is first and foremost a political fiction and a metaphor of the tensions between the individual and the collective, the 'landscape' is an ecological fiction which covers up a number of other, possibly more fundamental conflicts. As such, throughout the centuries the landscape can be interpreted as the battlefield where the interests of mankind dominate the regularities of nature. The landscape is framed, excerpted and consequently constructed nature. Yet, at the same time, the landscape is continuously mobilized in art and in culture in function of a radical negation of this manipulation. As time goes by, the myth of the untouched landscape has become a time-honoured tradition and has developed from the bucolic poetry of Virgil over the 'homeland' paintings by the Flemish expressionists into the television programme 'Vlaanderen Vakantieland'. Also in 'Variant', the 'Magazine of Vlaamse Ardennen.be' which focuses on 'Art & Zwalm' in the first issue, glossy colour photographs of idyllic landscapes predominates. Bicycle routes, regional gastronomic specialties, picnic spots and exhibition tours are to lure the tired city dweller to this idyllic countryside. This' local leisure time magazine' is a splendid example of the degree to which nature and art have been reduced to leisure activities, as of late. However, this reduction results in both an idealisation as in a potential threat. For the fiction of the unscathed, idyllic landscape as it is pictured in the media attracts hordes of city dwellers and, in their turn, these exert pressure on the landscape and affect it. In the contemporary landscape, construction and destruction walk hand in hand.

The above process was described in 1968 by the architect Renaat Braem: "I f we are living in the immense paste of houses, we need the car to flee to the alleged free nature on Saturdays or on Sundays. Otherwise, we go live in this free nature to gradually have it deteriorate in the process." ("The ugliest country in the world'). The 'landscape' loses its innocence and only reveals itself to be an ideological construct when we perceive the very things that have been omitted (industry, pollution, urbanisation, traffic jams, fridge box tourism, criminality). By means of this elimination, the nostalgic landscape profiles itself as the very opposite of the harsh urban reality. Artworks can be inserted in these cover-up strategies by collaborating with these tactics of camouflage. Or, in certain cases, they can function as potential disturbing factors and jamming stations which can shed light on ideological concepts such as land and the landscape in a less self-evident context and in the process deconstruct them. In principle, exhibition projects such as 'Art & Zwalm' are apt occasions for this process because of their abovementioned specificity. A potential network of meanings develops as art, land and landscape engage in a temporary linkage. One can retrace the lines of development of this process or one can react against it. The latter brings us back to the walk.

Nice picnic spots (an intermezzo a la Rousseau)

I was alone and penetrated deeply into the crevices of a mountain, and wandering from one grove to another, from one rock to another, I arrived at a clearing which was so hidden that I have never seen anything more wild in my entire lifetime. Black spruce and enormous beech trees, some of which had collapsed with old age and lied intertwined, they locked off this secluded place as an insurmountable blockade. Some apertures within this thick wall only showed perpendicularly steep rocks and vertiginous abysses and I only dared look into these when lying on my stomach. Long-eared owl, little owl and lich owls were screeching in the crevices of the mountain, some rare, yet familiar birds somehow moderated the haunting character of this desolate place. I was able to find dentaria heptaphyllos there, cyclamen, the bird's nest orchid, lacerpitium magnum and some other plants which fascinated me and diverted me for a long stretch of time. But, as I was overpowered by the strong impression which these things exerted upon me without realising it, I forgot about botany and plants and sat down upon cushions of lycopodium and moss and started to feel more at ease and dreamt away, thinking that I found myself in a hiding place over there which was unknown to the entire world and where my persecutors would not find me. This thought was tinged with a sense of pride. I compared myself to the great travellers who discover an uninhabited island and, quite content, I thought: indubitably I am the first human who ever ventured thus far over here. I almost considered my self to be a second Columbus. Whereas I waxed with pride at this very thought, I heard a certain rattling sound, not too far in the distance which I thought I could recognise. I listened, the noise repeated itself and became louder. I was quite astonished and curious and got up and made my way through thick shrubs and , at about twenty yards from the spot where I thought I had set foot as the first person on earth, I discovered a stocking manufactory.

This anecdote from Rousseau's seventh walk is not only quite funny, it is also remarkably pertinent. It seems as, in this passage, the philosopher is mocking his own idealistic glorification of nature and appears to suggest that unspoilt nature, one of the very basic tenets of Rousseauian romanticism is but a myth. In this wayward anecdote, romanticism tips over into its very antithesis: realism. For, by means of the sobering anticlimax of the stocking manufactory, Rousseau deconstructs the image of nature which he himself had construed. By continuing the promenade for a few more steps, the idyllic place which he had 'discovered' at once is reduced to the backyard of a factory. This is the very feeling of disenchantment which we all have experienced when happening upon an illicit dumping ground during a 'nature walk'. Yet, this disenchanting, irreversible but critical insight can only be reached by means of the walk. Whoever is walking, is moving through contexts, and this does not only takes place physically, but also on a mental level. While Rousseau was waling, he was pondering about his life. His moving in space is linked with a moving back into time.

As such, his walk becomes wayward. It leads to sobering insights.

In this sense, the walk (the promenade) is the opposite of the parcours, the planned and ready-made track. (With regard to this subject, cf. my essay 'Spoils of the park. The Park as occupied Territory, in: 'Zoersel 2002. Een raadsel voor Zoersel', 2002). For a wanderer is a migrant. He frees himself from fixed and imposed constraints and leaves the beaten track. He is the moving outsider. For whoever moves cannot be caught. Hence the negative political connotations of words such as migrant, fugitive, allochtonous, asylum seeker and gipsy. By moving about, the nomad finds himself back in a power vacuum and he evokes anxiety and ire with the sedentary autochthonous population. Thus, the other great theoretician of walking, the philosopher Ton Lemaire describes the walk as the 'praxis of space', as opposed to the view which, according to him is a 'theory of space' ('Filosofie van het landschap, 1970). In this sense, the walk could be considered as a form of applied ecology.

After his passing away, the character of Jean-Jacques Rousseau is blown up to mythical proportions. Little can be noticed of the walk as a reflexive and a critical act in the romantic recuperation of Rousseau. A striking example of the romantic glorification and recuperation of Rousseau is 'Voyage à Ermenonville' by Arsène Thiébaut-de-Bernaud which was published in 1819. As its subtitle 'Containing unpublished anecdotes regarding J.J. Rousseau, the lay-out of the gardens and the flore a Ermenonville as published for the first time' learns us, this curious book which is subdivided in eight 'promenades' constitutes a 'doct', yet at the same time 'sentimental' travel guide to and into the estate of Ermenonville, where Rousseau had spent the latter years of his life and where he now is buried. After his passing away, the park, which was laid out in British manner as a picturesque landscape garden becomes a true place of pilgrimage for Rousseau-admiring romantics. The book by Thiébaut-de-Berneaud adroitly addresses the myth of Rousseau and contains a complete list of the local flora, a description of the trajectory Paris-Ermenonville, hints for starting up a herbarium, a detailed description of the landscape park, some pages of appropriate scores and a great many literary and philosophical anecdotes. The included plan of the park on which all places of interest are marked can almost be read as one of a romantic amusement park. It goes without saying that no mention is made of Rousseau's revealing stocking manufactory; all the more so of sources, grottoes, cenotaphs, islands, burial tombs, temples of philosophy, huts of hermits, mills and poplars. Rousseau's wayward and subversive promenade has degenerated into a tourist parcours, replete with the prescribed and ready-made experiences.

Deliciously homegrown (Long vs. Smithson)

Yet, as we pointed out before, the walk does have a critical potential. Consequently, it ought not astonish us that the avant-gardes of the twentieth century made use of the walk as a strategy of subversion. But the ways in which the walk is undertaken in art, reveal quite a lot about the attitude of the artist with regard to his surroundings. In the middle of the sixties, the Dutch artist Stanley Brouwn acted as a lost urban tourist and had himself explain the way to a given place in drawing by passersby and later exhibits these sketches under the denominator 'This way Brouwn'. In his 'following pieces' of the end of the sixties, the American performance artist Vito Acconci makes a persiflage of the 19th C city stroller, intending to follow and unknown person to the very moment when the latter enters a house. (Sophie Calle, in her turn, will have herself followed for some time by a professional bureau of detectives and afterwards exhibits the resulting textual and visual documents about her wheeling and dealing.) Yet, it is first and foremost the 'walk in nature' which will inspire a number of artists towards the end of the sixties (and it is no coincidence that this is also the time when the abovementioned diatribe by Renaat Braem was published) to get alternative ideas and visions. 'No walk, no work' is the motto of the British artist Hamish Fulton who, together with John Long initiated British land art. "I thought that art barely paid any attention to the natural landscapes which cover this planet, nor that it made use of the experiences which these places have to offer", Long writes at the beginning of his oeuvre. Ever since, the walk and trekking have constituted his artistic strategies 'par excellence'. On this occasion, he usually looks for solitude. In his sculptural projects and in his photo works, in which mankind stands out by its absence, the gap between urban culture and nature is being visualised in explicit manner.

It is striking to see that both British and American land art from about 1970 both constitute symptoms of a neo-romantic relationship towards the landscape. Yet, at the same time, both traditions are the incarnations of a radically different approach. Long and Fulton make use of the landscape as an alternative of the city and visualize it in its 'pure' state of virgin naturalness. In the process, they make use of the photo camera, pencil and paper. They adopt the stance of Rousseau when discovering and temporarily taking hold his untouched spot. The myth of the landscape is left intact while doing so. Quite to the contrary, the American earth workers (Walter De Maria, Robert Smithson) are rather fascinated by traces of human activity within the landscape. They make use of a bulldozer and of an excavating machine to bring about large-scale transformations in the landscape. In their work, the power of man over nature is not being camouflaged: they prefer the shocking view of the stocking manufactory. The landscape is battered both physically and conceptually. Especially Smithson reveals himself to be a radical aesthete of the hybrid and of the impure in his earth works and in his writings. This comes to the fore in a revealing manner in the year 1969: whereas Richard Long is making a documented trekking trip of three days in the countryside of Wiltshire, Robert Smithson has a truckload of tar run down a derelict quarry in the vicinity of Rome. As opposed to Long, Smithson conceives of art as a possible link between ecology and industry. "Ecology and industry are no one-way streets, in fact hey out to be at crossroads. Art can be an auxiliary means, mediating between the ecologist and the industrialist." The splendid descriptions of industrial wastelands by Smithson are in no way inferior to the sublime rhetoric of the landscape of romanticism. By recognizing the hybrid and the impure, Smithson's walks are in essence more wayward than those by Long, for they acknowledge the construed, fictitious character of the natural landscape and, by doing so, are a weapon to prevent the ideological use thereof. Upon closer consideration, the Brit Long and the American Smithson constitute a 20th C variation of the 19th C cultural inheritance of their cultural inheritance in their respective way of dealing with nature and with the landscape. It is the attitude of Constable as contrasted with the one of the Cowboy.

The battle of Gavere (rise and fall of the exhibition as a walk)

In 1971, both artists, Long and Smithson are participating in an exhibition which will go down in history as the mother of all 'wander exhibitions': Sonsbeek 71. The consequent choice of the organizers and of a number of artists for site-specific interventions made this edition of the Sonsbeek sculpture exhibition fundamentally different from the previous one. The project covers the entire surface of the Netherlands, not only the Sonsbeekpark at Arnhem. For this reason, the subtitle will be 'Sonsbeek buiten de perken / Sonsbeek out of bounds'. The development appears to be this drastic and far-reaching that the notions of 'manifestation' and 'activity' surfaced to replace 'exhibition' and for the occasion, the term 'sculpture' is replaced by 'space and spatial relations'. Consequently the catalogue is published in two parts: one with proposals and maps, a subsequent part contains views of the realisations. Some artists realise a book or a film, others limit themselves to a conceptual contribution or a statement in a magazine, a journal or in the catalogue. Other artists opt for radical interventions in the park or in the Dutch landscape. Richard Long draws a temporary, white 'Celtic sign' in the landscape of the Schiermonnikoog Island. Robert Smithson realises a permanent, monumental 'Spiral Hill' and a 'Broken Circle' in a derelict sand quarry at Emmen. Amongst other things, the genesis and the reception of Sonsbeek 71 show this project to be unique in its category, with all its ensuing consequences. Out of sheer necessity, a number of projects was not realized. The press, the public and the political authorities reacted in too uncomfortable a manner to the new format and to the new forms of art, amongst which land art and concept art. A true witch hunt against this project was orchestrated by traditional visual artists' unions. In this sense, the first wander exhibition was a subversive exhibition, both artistically and ecologically.

Sonsbeek 71 copies the critical and dynamic activity of the nomadic artist and applies it to the exhibition concept as a whole. In the process, the classical museum 'parcours' of the conventional exhibition of sculptures needs to give way to the alternative, individual 'promenade'. From then onwards park and city exhibitions have increasingly called upon the powers of thought and of walking of the visitor: Skulpturprojekte Münster, Chambres d'Amis, Over the Edges and a number of smaller city, park and landscape exhibitions came into being from the eighties onwards in - amongst other places - Zoersel, Tielt, Leuven, Watou, Aarschot and Zwalm. In the process, and just like the classical exhibition of sculpture from before (Middelheim Biennial, Sonsbeek before 1971), the wander exhibition has become a convention. As of today, each and every community or city wants to have its own 'contemporary art project' in the form of a biennial or a triennial. Resourceful art lovers have the opportunity to discover the city or the region in question, thus allowing the local trades people to have their share in the undertaking. But the community which organizes the event is primarily getting symbolical capital. To a great many, contemporary art is still evoking associations with dynamism, progressiveness, and open-mindedness. In this sense, contemporary parcours exhibitions are often exposed to the forces of political and economic recuperation. Quite often, the democratic myth of 'public space' and the ecological myth of the 'landscape' are mobilised in professional manner. By doing so, the act of walking has lost its subversive power of reflection and contextual criticism. It has become a form of passive consumption and has become part of the predominant culture of leisure. If Rousseau were to leave his idyllic spot at the present day, he would not confront a stocking manufactory, but a work of art.

The ideal combination culture-nature (a conclusion)

Just like the 'experimental' promenade by Rousseau had become a romanticist figure of style in the course of the 19th century, "the subversive strategy of walking of late-modern avant-garde from about 1970 has lead to the popular type of the contemporary, postmodern 'wander exhibition'." In both historical developments, the thorny aspects have disappeared and the product is polished. As of today, wander exhibitions appear to be more popular then ever. They constitute a non-negligible factor in the 'unveiling' (and the consumption) of contemporary art (and of the contemporary category of the rural). At the same time, the radical and experimental character of this exhibition strategy definitely seems to belong to the past. In the best case, the wander exhibition provides a pleasant and approachable way in which to consider contemporary art. But does this suffice? For this reason, we have to ask ourselves whether the artwork or the landscape actually derive any use from the wander exhibition. In other words: are both bestowing fundamental surplus value to each other or do they merely tolerate each other? Do the artwork and the landscape interact with each other or are they functioning alongside each other? At times, the contemporary wander exhibition appears to be a romantic flight from the museum and (hence) from the city. Whereas this fight had a romantic-critical dimension in the late sixties, at the time of Long and of Smithson, as of today this dimension appears to be rather romantic-nostalgic. Whereas the landscape had the function of a laboratory at the time of land art, and the spectator acted as a motivated participant, the contemporary landscape rather seems to be a picturesque décor and the visitor to the exhibition appears to be a tourist of the region.

Only in rare cases, works of art manage to bestow the landscape with surplus value, and vice versa. Whereas each landscape is a goldmine/minefield of different meanings, works of art only sporadically manage to drill into the subterranean economic, ecological, social and political arteries. The overabundance of regional and park exhibitions provides part of the professional public with a feeling of saturation. On the other hand, artists almost feel obliged to participate in open air exhibitions, even if they show little or no affinities or experience with site-specific or environmentally oriented strategies. Whereas the exploration of the landscape was a radical, personal and artistically argumented decision in the late sixties and the early seventies, over the past years it appears to be more of an extraneous constraint. Maybe it is time for us to leave the tired and overexposed landscape in peace and to direct our critical attention to the somewhat neglected museum. And yet, the project 'Kunst & Zwalm' manages to somehow escape from the current malaise of the wander exhibition. This is due to its social component. The integration and interaction with the local community undeniably bestow an extra dimension to this project. It is not so much the overburdened relation between artwork and landscape which seems to be essential to me within this context, but rather the intense relation between the locals and the art project. This social aspect, namely the creation of a local connection of the population with this initiative appears to be a challenge for future other city or regional exhibitions to me. If this aspect were to be dealt with in greater depth on the occasion of subsequent editions, 'Art & Zwalm' could have an experimental function within this context. For even the most 'lonesome' wanderer is moving about in a social context.

Johan Pas, Ekeren, December 2003, Translated from the Dutch by Yonah Foncé

- Footnote: all subtitles have been borrowed from Variant.Vlaamse Ardennen.be Magazine, nr. 1, July-August-September 2003